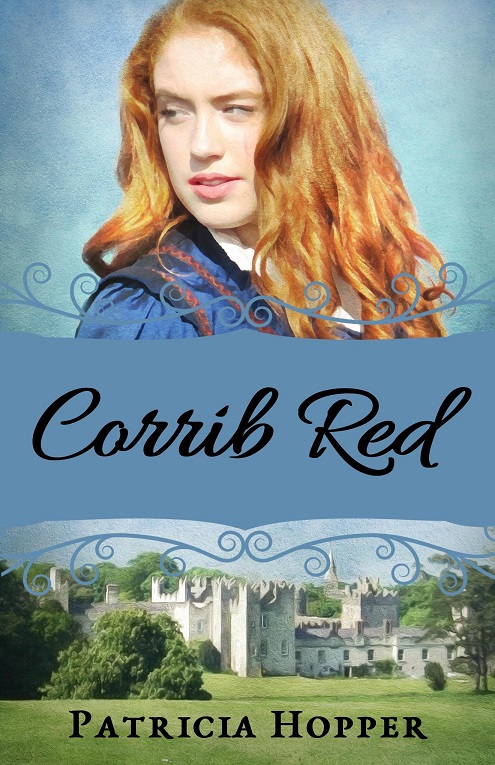

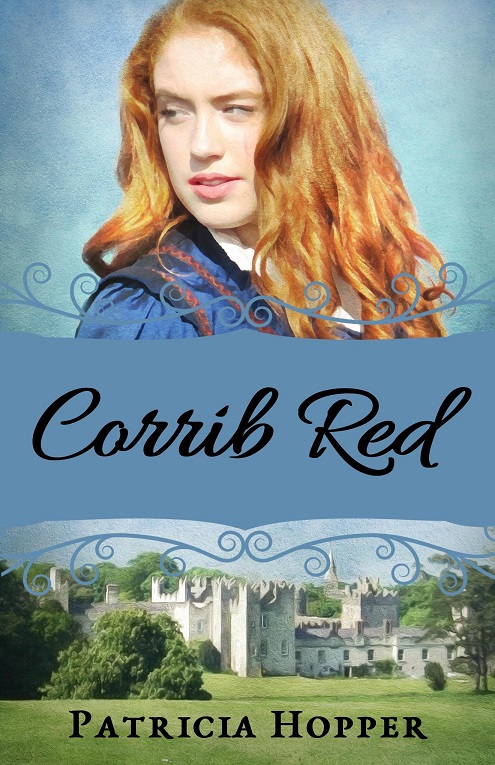

Joining me this month is West Virginia author Patricia Hopper Patteson, whose new book Corrib Red comes out in March.

Who are you? Where are you? What kind of stuff do you write?

Hi, I am Patricia Hopper Patteson. I am what you might call a tenement rat from Dublin, Ireland. For the first few years of my life I grew up in what is now the trendy part of the city called Temple Bar. Way back, this area of the city was known for its sub-standard tenement flats. At age seven my family moved from the city to the suburbs. I came to Morgantown, West Virginia as a bride back in the 70’s and have been here ever since. I write non-fiction, short fiction and novels.

How does your transatlantic background inform your writing?

Having a transatlantic background (love that term) is like speaking two languages in a way. I behave differently depending on whether I’m here or in Ireland. Living abroad certainly affects how I write and what I write about. Interestingly, I received my undergraduate and graduate degree from [West Virginia University] as a non-traditional student. So my introduction to creative writing came from WVU. My core introduction to story-telling comes from my parents, who made up stories to tell us as young children.

This trilogy at the core is about emigration. About the Irish in earlier centuries who came to the US but never returned home. That’s what the first book is about—returning home. Whatever extra money the Irish had after they emigrated was sent home to help the family survive. Many emigrated out of necessity in a time when travel was difficult and money was scarce, unlike today where we have so many ways to stay connected to family and friends

Tell us about your most recent book, story, or other project.

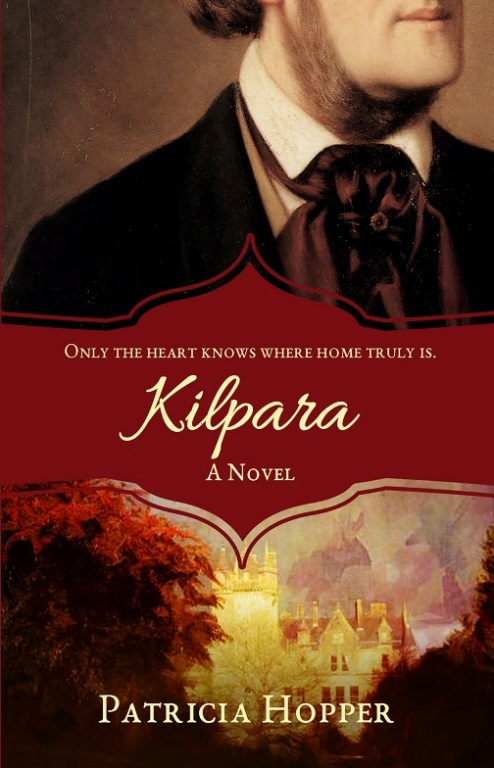

Kilpara is my first novel in a three-part historical nineteenth century family saga series. It takes place in both the US and Ireland and begins in Maryland in 1866 right after the Civil War. The second novel called Corrib Red is due out in March and is the second novel in the series. It takes place almost completely in Ireland and jumps a generation to two sisters who are coming of age and face the dilemma of choices available to them within the period constraints. The third novel in the series starts ten years later and takes place in both Ireland and The US. An illegitimate African-American daughter is central to this story that comes together in Ireland and throws the family off center.

I’m intrigued by the span of time you plan to cover in your family saga series. Was that always the plan, or did the specific stories you’re telling just work best in those periods?

The first book was initially two stories and everyone that read it said it should be two separate stories. So when I began fleshing out and editing Kilpara I found out I had enough material to make it a complete novel, so the story reads that way.

I love anything to do with the US Civil War and the first novel begins right after the US Civil War (1866). When I was growing up I never heard anything about the Irish in the US Civil War. I was surprised when I first went to Antietam and Gettysburg to learn how many Irish fought in that war. That’s why I chose that period.

I jump a generation for the second novel Corrib Red which takes place mostly in Ireland (1885). This is Parnell’s time, and I’ve always loved what he did for Ireland, and how tragic it was that he died young. Many Irish turned against him when they learned he was involved with a married woman, whom he later married before he died. His history gives great insight into the culture and mind-set of the time.

The third novel (in-progress) takes place about ten years later (1896). This was a time of cultural awareness in Ireland that later influenced history in the early part of twentieth century.

In what genre do you primarily write? Why did you choose that one?

Right now I’m primarily writing historical fiction, but I have other projects started like mystery, romance and young adult. I find historical fiction fascinating. Although the 19th century was a less complicated time, it’s hard to imagine living without the conveniences we have today. People were far more interactive because they had less distractions and outside commitments. Just think, women who could afford servants, spent much of their day changing clothes for different events, breakfast, lunch, walks, visitors, dinner. It seems exhausting by today’s standards especially now when you can just put on a pair of jeans and go. Women were also restricted by societal norms and were treated like property by the men they married.

Tell us briefly about your writing process, from once you’ve got an idea down to having a finished product ready for publication.

The idea for the novel is the easy part. It’s developing a whole concept for a novel that’s the challenge. Once the concept for the beginning, middle and end begin to gel in my mind I start to outline the story. I generally like to start the first couple of chapters to get a feel for the characters and story at the same time I’m fleshing out the outline. After the first couple of chapters I finish the outline completely so I have a guide. On this third novel I’m trying something new which is telling the story from two POVs and switching from first person to third person. To make this work I’m doing alternating chapters—so it’s a bit of a challenge. I go through many edits of the novel starting with content, then grammar and proofing. After about the third or fourth edit the book starts to take shape. The last thing I do is read the whole novel out loud.

What do you get out of that process that you don’t get from just reading it with a red pen in hand?

When I edit with a pen I hear the story in my mind. However, when I read the novel out loud, I hear each word I speak. I prefer it if I can get someone else to read the story out loud, because then I really hear things more. But that doesn’t always happen. When reading out loud I can hear words that are unnecessary, phases that may be too long, and ramblings that may need to be tightened, scenes that could use some tidying up, and the pacing. I work on all of these things during the editing phases, but reading out loud helps me find anything I may have missed.

Who is the favorite character you’ve created? Why?

I have two favorite characters in the family saga series, although I must say I like all of the characters. The two that are most challenging are Cecil and Aunjel.

Cecil is a 19th century sociopath and very evil. I always love to read about evil characters in novels and look for their redeeming qualities. Cecil doesn’t have any redeeming qualities. He thinks he’s above everyone and everything and takes revenge on anyone who goes against him in a major way.

Aunjel is one of the two main characters in book three of the series and she’s the daughter of Lilah, a light-colored African-American. Lilah has a mutual liaison with Ellis O’Donovan, an aristocrat and major character, in book one. Aunjel is the result of that liaison although Ellis doesn’t know about her until book three. Aunjel also grows up believing her biological father is an African-American. To create Aunjel I wrote a 13,000 word story about Lilah, Aunjel’s mother, and her background, so that I could better understand Aunjel and her challenges in the late 1800s

What’s the weirdest subject you’ve had to research as a writer that you never would have otherwise?

In book three of the series I send David Ligham, a fairly major character in book two, away to West Africa to negotiate a peace treaty with King Prempeh of the Ashanti tribe. This is fictional of course, but there was a lot of conflict going on between the British and the Ashanti tribe around that period. I read three books on the subject to write a few paragraphs.

What’s the one thing you’ve learned, the hard way, as a writer that you’d share to help others avoid?

There are many things a writer learns along the way that it’s hard to know where to begin. The importance of editing is the one thing that helps establish a writer and gets them recognized. Also, if you find another writer who you trust completely to read your novel, or short fiction, and give you honest feedback, this will help avoid weaknesses in your writing.

If you won $1 million (tax free, to keep the numbers round and juicy), how would it change your writing life?

It probably wouldn’t change things all that much. However, I would love to write a novel set around the Grand Canyon, and it would be nice to spend time there to research the area.

What’s the last great book you read or new author you discovered?

One author I had heard about, but hadn’t read any of his work is Ken Follett. I recently read The Man from St. Petersburg and thoroughly enjoyed the novel. In this novel Follett brings London to life in the early 1900s, and the characters and plot are intriguing.

What do you think your next project will be?

I’d like to write a historical romance that takes place in present time, and I’d like to write a young adult mystery novel.

How would you write a historical romance that takes place in the present time? That sounds like a contradiction in terms.

Sorry about the contraction of terms. I may have been a bit lazy. It’s really a modern day romance with historical undertones.

For example a situation that takes place in today’s world that is parallel in some way to Abraham Lincoln’s unfortunate assassination. The male protagonist won’t be a president, more likely a congressman or a senator, or even a mayor. He will try to save a small town from being overrun by corrupt business associates. These associates want to move a gambling casino into the town as a front to launder illegal money. The female protagonist would be the conduit between the present and the past. She would discover a dress worn by Mary Todd Lincoln tucked away in her great-aunt’s attic. Every time she puts on the dress (or maybe just touches the dress) Mary Lincoln’s ghost appears to warn about danger. Mary’s ghost will help the female protagonist avert the assassination of the present day male protagonist. This of course pushes the male and female protagonists together.

This the long way to explain what I mean. It’s a story I’d like to write but haven’t figured out the complete concept yet.

Patricia on Social Media

On the Web

On Facebook

On Twitter

On Linkedin

Get Kilpara at Amazon or Barnes & Noble

Learn more about Corrib Red at Cactus Rain Publishing