Joining me this month is a local purveyor of spooky tales about weird, wondrous, and just plain weird things.

Who are you? Where are you? What kind of stuff do you write?

I am Eric Fritzius, a freelance writer, actor, director, instructor, podcaster, and playwright living atop a hill in Greenbrier County, W.Va. I’m the outgoing secretary for West Virginia Writers, Inc. an organization in celebration of writers and writing in Appalachia. I write short fiction, short nonfiction and short plays primarily. Occasionally my writing is published and my plays performed.

How does your work in the theater, as a writer, actor, and a director, influence or inform your short story writing?

Tremendously. From elementary school, my earliest form of creative writing was writing plays. My dad did community theatre, so I got to see him act in The White Sheep of the Family and The Man Who Came to Dinner. I would follow along with the script to help him learn his lines, which was the first chance for me to see how a play is constructed on the page. I was fascinated and immediately began trying to write my own. I had no idea what the story would be, but my 4th grade mind wanted it to include Mission Impossible style mask removal, with characters revealing themselves as other characters. In other words, it was unstageable and remains unfinished. (Okay, I may admit to that one being a failed project.) In high school I started attending a drama camp in which we wrote a three act musical comedy in the space of a week. That was like going to boot camp each year. You had to learn to tell complete stories using only dialogue and stage directions, with limited storytelling because you’re mostly limited to one set and therefore one setting. You also had to learn what plot points your characters should summarize and which ones to portray, cause you had a definite limit of how long the play could run. And I learned a lot about using music to help tell the story. After seven years of that camp, I developed an ear for natural sounding dialogue and the rhythms of speech. And when I began writing prose, it tended to be dialogue heavy. To the point that I’ve adapted a couple of my short stories for the stage and have experimented with adapting a stage story to prose.

All writers are supposed to get into the heads of their characters and know their motivations. But acting as a character tends to turn this process up a notch, because that’s essential to the job—particularly when you’re playing characters without a lot of dialogue, as I have often done. It’s not enough to just do what the script describes your character doing and saying, you also have to know why they’re doing and saying it in order to portray it accurately. And that’s rarely spelled out for you in the script. Similarly, as a director, I have to be in the heads of all the characters in order to make the play work and appear to be happening as naturally and logically as I can. Which is basically what writers do with their stories, except with prose the limiters of set and time get removed and you have an unlimited budget to work with in terms of set. And, in genre, an unlimited special effects budget.

Tell us about your most recent book, story, or other project.

My most recent book is also my first; a collection of short modern fantasy fiction called A Consternation of Monsters. It was recently published as an audiobook, for which I did the narration.

How did you come to produce your own audiobook version of Consternation and were there any stories that presented any hurdles in shifting them from the page to the aural realm?

Having a background in radio, podcasting, and acting, I thought that doing audiobooks would be no sweat. I have a small home recording studio which I had already to record a few stories for my promotional Consternation of Monsters podcast. These weren’t audiobook recordings, per se, but instead recorded live readings at author events, recordings of stage adaptations of my stories, or were audiobook/radio drama hybrids, complete with sound effects and sometimes other people playing roles. To record a mere audiobook, I foolishly thought, would be a step down in difficulty.

Before I attempted it, though, I was hired to record an audiobook for author S.D. Smith for his middle-grade novel The Blackstar of Kingston. He and I had met a few months earlier and I was very impressed with his debut novel The Green Ember–a fantasy series he describes as “rabbits with swords”—and he enjoyed my podcast work. He already had an audiobook for The Green Ember, skillfully narrated by Joel Clarkson. However, Blackstar was a prequel to Ember, set a century before. It made sense that it could have a different narrator as it shared no characters.

Recording Blackstar was a true learning experience, and a humbling one at that. All of the acting, broadcasting and narrating expertise I thought I possessed seemed to evaporate in the face of portraying a dozen characters, in a variety of accents from across the UK, while also maintaining the level of tension and intensity that some of the chapters required. I would sit at the mic, furious with myself for my inability to get my mouth around simple words, or at the disgusting smacky noises I kept hearing in every syllable, or at the UPS driver daring to make his deliveries in my neighborhood, whose truck my mic easily picked up. I wound up recording the whole thing twice and then re-recording some of the individual chapters three or four times each before I was happy. (Fortunately they were short chapters, the longest of which might take fifteen minutes to read.)

The major learning curve was in engineering the recordings to the standards of ACX.com (which is Audible’s self-publishing arm for audiobooks). This wasn’t like a podcast that you could record, edit, upload and walk away. You had to have a consistent product across all chapters, with all audio files falling within the same range of levels. I wound up being quite proud of the end-product, but it was far more difficult to achieve than I had thought. It was great experience to have, though, before recording the stories for Consternation.

I recorded and edited all but my final two stories in early 2016, just a month after finishing Blackstar. Then I got royally busy casting and directing a play festival, then a number of other jobs, and wasn’t able to get back to it until November. By then I needed a refresher course on how to engineer the files and found a good tutorial source. Unfortunately, it was too good and my new recordings sounded better than the ones from January. I had to re-record everything using the new techniques. Then, just when I thought I had everything recorded, edited, and mastered, I wound up accidentally saving the brand new version of “The Wise Ones” on top of the newly recorded and edited version of “Old Country.” (What can I say–both involve other-worldly mobsters and they got mixed up in my noggin.) Fortunately, I had an unedited backup of the “Old Country” file, so I didn’t have to start from scratch, but it was a mistake that cost me several hours in editing and mastering.

In what genre do you primarily write? Why did you choose that one?

I tend to write modern fantasy, but I was kind of drug kicking and screaming into it. Growing up in small town Mississippi, I was mostly a science fiction fan. I was drawn to stories of ordinary people who were pulled out of their boring daily routine and thrown into adventure. I cut my teeth on reruns of `70s era Doctor Who (only a handful of years after their original broadcast, really). Tom Baker was my Doctor and his remains my favorite. From Who, I found my way to Douglas Adams’ work, after mistaking an episode of the Hithchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy TV series for Doctor Who due to the BBC video production “look” they shared. I loved it and soon devoured all the books. This then led me to Neil Gaiman, who had written a nonfiction biography of Hitchhiker’s in the late `80s called Don’t Panic (in which 8th grade me was astounded to learn that Douglas Adams used to work on Baker-era Doctor Who).When Gaiman began writing comics, I remembered his name and started picking up his work, reading The Sandman, and Black Orchid, following on to his early novels Good Omens (with Terry Pratchet), Neverwhere and have been a fan since. Back then, I dreamed of writing funny sci-fi, like Adams. And if anyone were to ask if I was “into” fantasy, I would deny it with vehemence because I thought of fantasy as sword and sorcery. But I loved Gaiman’s ability to create wondrous and often dangerous worlds that seemed to be just on the other side of a veil from our own. And his books were definitely fantasy, moving beyond magical realism into Gods and monsters walking around modern earth. Like my other favorite, Ray Bradbury, he took the ordinary dull world and revealed that the strange and wonderful existed within it. His characters often began in an ordinary, dull existence, but were pulled into adventure, usually with an enigmatic guide or two to show them the way. Great shades of Doctor Who, really. And the fact that Gaiman has gone on to write for the modern Doctor Who makes me immensely happy.

I also write mundane stories, though, where nothing strange or supernatural happens at all.

What determines whether a story is “mundane” or has supernatural element? Does the supernatural element lead to the story or does the story demand something out of the ordinary?

A mundane story, to me, is any story lacking genre elements, or any sort of magical realism. Doesn’t make it boring by any means—as the term mundane has come to be thought of—but just a story grounded in reality.

I find writing mundane stories more of a challenge than genre stories, but the temptation to try and turn them into genre stories against their will is often strong. With genre, writers often have an instant hook of the fantastic that will keep a certain demographic of reader—fans of genre—reading. Without those elements, I feel like I have to do more heavy lifting in order to make my worlds and characters real and interesting enough to hook the readers of all. Now this shouldn’t be the case, because writers of genre fiction are supposed to do this same kind of heavy lifting in addition to the world-building necessary to bring the fantastical elements they include to life. Somehow, though, what should be easier on paper seems harder to me. I’ve found myself mid-way through a mundane story before, have hit a snag in my narrative and have thought “Oh, if I could just have Miss Zeddie show up now I’d be home free and could crack this story, no problem.” In those situations, I know I have to stick to the mundane because to do otherwise would be cheating the story somehow.

Seems strange to say it, but I don’t think I’d ever considered if there is a difference in writing technique between my mundane stories and genre stories, or if the genre elements themselves are what leads to the story or vice versa. There are no mundane stories in A Consternation of Monsters, though there is one (“Puppet Legacy”) that is 95 percent mundane, with a hint at larger genre elements, and a feint at others. In 9 out of the 10 stories, though, it was the genre element that inspired the story. By contrast, many of my mundane stories (which I nearly have a collection’s worth gathered), are often, though not always, character-driven first with the stories building out from there.

Tell us briefly about your writing process, from once you’ve got an idea down to having a finished product ready for publication.

My process, if you’d call it that, is pretty varied and can sometimes take years and I pick up and put down a given story until it’s finished. For every short story I have been able to dash off a draft in an afternoon, I probably have five that have taken months or years to finish. (I find it’s best to have a hard deadline with embarrassment on the line should I not meet it.)

However, I find my ideas often start as a glimpse of an image in the middle of a story, which I have to then write up to, figuring out how that image comes to be, and then write beyond it to see what happens next. For instance, back in the mid oughts, my wife and I went on a glacier tour on Resurrection Bay, near Seward, AK. The scenery was gorgeous and inspiring on its own, and we got to see some pretty big wildlife up close, including whales surfacing near the boat. On the way back to Seward, the boat moving along at a faster clip, I found myself imagining what might happen were a blue whale to burst out of the bay, directly in our path? It was an image, but not a story. Even if something catastrophic happened to the boat, like it capsizing, it was still just an incident with no inherent conflict. But what if, I continued to wonder, the hypothetical whale had surfaced in order to exact vengeance upon a specific passenger? Not so much in the way of the 1980s killer whale movie Orca, in which the titular creature exacted revenge on Richard Harris (and Bo Derrek’s leg, to some degree) for killing his mate and child. More of a Day of the Jackal, except with a whale as the assassin. That was the point when I realized it wasn’t really a whale to begin with. And then some new, exciting, and improbable images entered my noggin. At this point I had some basics, but the ultimate story itself wasn’t cracked for months yet.

Probably a year later, I took an online test to see if I might be a good candidate to become a transcriptionist. (I type nearly 100 words per minute, so it seemed a skill that might have value.) The test required you to listen to a sample recording and transcribe it exactly, including making notations for any stray noises in the room, such as coughs, farts, sneezes, etc., with those sounds described in [bracketed text] on a separate line. The transcription folks never called me, but knowing the format of a transcription gave me the key into my story of the whale/non-whale in Resurrection Bay. In an instant I knew who my main character was, and how to get into and out of the story. The rest of the details in between those points filled themselves in as I went.

This became my short story “The Ones that Aren’t Crows”, (which can be heard as a podcast at my website).

Sometimes, though, I’m lucky enough to have stories arrive in my head fully formed. “Limited Edition,” which is the longest story in my book, dropped into my head, almost fully formed after I read a single sentence. It was a writing challenge issued to me by a friend, who said I had to write a short story in which the following sentence appeared: Something told him that in all the world, there was no other fork quite like this one.

When you set aside stories and then come back to them later, do you always intend to come back to them or, when you set them aside, do think they’re failed projects that just aren’t going to work?

I don’t believe in failed projects. I insist on believing that all stories can be made to work. Eventually. However, the number of story fragments in my NPROGRESS directory would seem to argue otherwise.

I read a piece from Neil Gaiman in which he describes trying to write his novel Coraline on a few different occasions. He’d come back to it every now and then, averaging 2000 words a year, and make a little more progress only to find he did not yet possess the skill to write further. After 12 years he said he decided that he wasn’t likely to get any better than he was in that moment, so he may as well get on with it and finish it. I can absolutely sympathize with this. I definitely have begun stories that I didn’t possess the skill to complete at the time. Some of these have to gestate for a while, with occasional revisits by me until one day something just clicks and I’m able to finish it. Or I don’t.

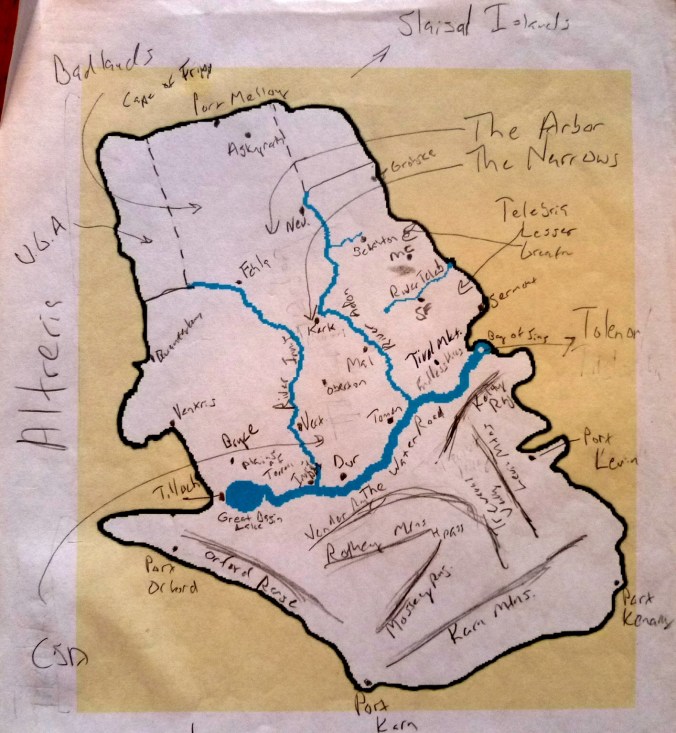

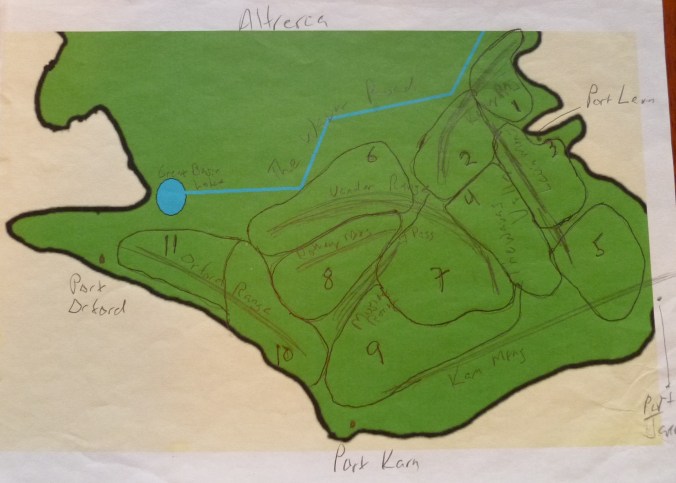

Of the stories in Consternation that falls into this category is “Old Country,” a story I started in the late 1990s as a way to flesh out a particular corner of the history of the shared fictional universe my friends and I had created. It began with the idea of a guy the mob is unhappy with being called in advance of his own hit, just to make him squirm, and because they believe his knowing will make no difference in the outcome. The setting was the pre-cell-phone `80s, when a mobster could just call you at home and then have his henchmen cut your phone line afterward and hang out to make sure you stayed put. I knew what the turn of the story would be, and I knew how the guy would escape his fate. What I didn’t know was how to get from the phone call about the hit part and the escape his fate part. Seemed like it needed something special. And so the story sat there as a beginning and ending only for a few years. Somewhere in the mid-2000s, I met an older lady at a writing event who chatted with me for quite some time on the topic of quilting. It’s not a topic I have a lot to offer on. So after I exhausted the story of my own grandmother taking up quilting later in life, and then officially retiring from it as soon as she’d finished a quilt for each grandchild, I was done. The lady, though, had quite a depth of knowledge on the topic and was willing to share it—all about spiral quilts and block quilts and patchwork quilts and art quilts, and on and on. Under other circumstances, I might have needed to gnaw off my own leg to escape (to paraphrase Douglas Adams). But instead, I was fascinated by her stories because of a secret she revealed to me as to her quilting process. The lady said that when trying to decide what style of quilt to work on, she would frequently be petitioned by the spirits of her dead family members, each of whom had an opinion as to what sort of quilt she should work on. They would apparently argue with each other, and with her, until she finally made a choice. Some days the spiral quilt “people” won. Some days the block quilt “people” won. It was a magical realism sort of moment for me, because she said it quite matter-of-factly, and with no reservation about telling all this to a stranger. It was awesome from a character-study standpoint. Thinking back on that conversation later, the elements of it merged into Martin’s grandmothers and their mystical quilting skills, and suddenly my story had the middle it was in need of.

Who is the favorite character you’ve created? Why?

Probably have to go with Miss Zeddie on this. She’s a wise old woman who appears in two stories in Consternation (including “Limited Edition”), and is referenced in a third, by a Mexican gray wolf named Fungus. Truth be told, though, I didn’t create her. At least, not initially. A friend from college, named Marcus Hammack, created her as a non-player character in a role-playing game my friends and I played. It was a game set in a fictional universe that we collectively created. Madam Z, as she was called, was an enigmatic, mysterious, and frustrating figure for our player characters to meet. On the surface she was just an odd, wise, yet still very cranky old lady. Somehow, though, she was simultaneously the most intimidating figure our characters had encountered. Marcus’s masterful storytelling skills implied a great deal of power in her, while at the same time showing only a tiny bit of that during the actual game. I was immediately curious as to her backstory, and kept trying to guess things about her over the course of our sessions. Ultimately, Marcus revealed that he’d developed no backstory for her whatsoever. She was a character he’d kind of created on the fly to help guide our characters because we’d obviously not picked up on the clues he’d been feeding us otherwise. I was disappointed, but, after he graduated, I became her custodian, free to apply the backstory I’d been dreaming up as I saw fit.

We meet the old cranky version of Zeddie in Consternation. A younger, less-jaded version of her will appear in the next collection. (Oh, and we’ve already met her brother.)

What’s the weirdest subject you’ve had to research as a writer that you never would have otherwise?

It’s been a goodly number of years since, but I had to research the ancient origins of the Mafia for my story “Old Country.” I couldn’t begin to tell you my sources at the time, but a Googling will bring up some that exist currently. Being the internet, there is, naturally, disagreement. But the version I chose to align with was one that speculated La Cosa Nostra began a few centuries back as groups of Sicilian farmers who organized to defend their land against the kind of repeated invasions Sicily has seen across its history. People think I made all that up for the story, but if you remove the dark warriors—who I did make up—you’re left with basic history.

I suspect, though, that the answer to this question will change once I have a draft on a different short story—another that I’ve been wrestling with for a few years. Its current title, “Draft of Chapter 13 from the Unpublished Memoir of Baron Ladislaus Hengelmüller von Hengervár, Austro-Hungarian Ambassador, 1894 – 1913” might give you an indication as to the era I’m researching. Despite its “assigned reading” sounding title, the story is an action adventure.

What’s the one thing you’ve learned, the hard way, as a writer that you’d share to help others avoid?

A lot of time and trouble can be saved by reading and taking to heart Stephen King’s On Writing. There are around six pages near the middle of the book (you’ll know them when you get there) where he breaks down some hard truths of the writing game that often take writers years to learn on their own. Or, indeed, accept. Some of the advice he gives I had heard from others before in regard to my own work, sometimes for years, and had either not believed the advice at the time, or just stubbornly refused to follow it. I’ve now come around. I teach Mr. King’s advice to my own students, giving full credit to Uncle Steve when I do. I then advise them to go read Ray Bradbury and see how gloriously and elegantly such rules can be broken by a master. I’m certain Mr. King would agree.

If you won $1 million (tax free, to keep the numbers round and juicy), how would it change your writing life?

I suspect I’d get even less writing done. Unless, maybe, I used the money to pay people to give me deadlines.

What’s the last great book you read or new author you discovered?

I’m super late to the party on the Kingkiller Chronicles. I’m not usually drawn to historical fantasy, though I have dipped into it more and more in the last decade. And I did my best to resist this series, too, despite multiple people whose opinions I respect telling me I would love it. It took hearing Patrick Rothfuss speak at the WV Book Festival last year before I realized I had been wrong the whole time. His talk was so good that I decided I was doing myself a disservice by not reading The Name of the Wind. So I picked that up and it’s fantastic, as billed. I had to buy autographed copies for a couple of the people who’d been telling me to read it for years, to make up for ignoring their advice.

What do you think you’re next project will be?

I’m currently directing a play called The People at the Edge of Town(May 19-20, 2017, at the Pocahontas County Opera House, in Marlinton)by WV playwright, A.J. DeLauder. It’s a play largely about small town politics, class warfare, friendship, and family secrets set in a town council chamber. After that, I have secretarial and contest coordinator duties to wrap up for West Virginia Writers, Inc. Then I hope to get back to working on my own writing and voiceover projects, including the next collection of short stories. It will likely have another inadvisable collective noun title, too. A Solace of Baba Yaga, maybe.

Where to Find Eric Online

Web

Facebook

Twitter

YouTube