I read these two books back to back because they seemed to go together. One is a sober telling of how an epidemic swept the nation, landing right in my back yard (the book itself swept through my office earlier this year). The other is a passionate call to arms about the War on (Other Peoples’) Drugs. Both are essential reading.

The Dreamland in Dreamland, by former crime reporter Sam Quinones, is a public pool in Portsmouth, Ohio. For decades it was a hub of life in the town, ever expanding. It’s decline was tied to the region’s decline as a manufacturing hub. As jobs went away and poverty grew, addiction to powerful new opioid painkillers, and then heroin, ravaged the region. Dreamland was the perfect metaphor, withering away to merely a memory.

In Dreamland the book, Quinones lays out the perfect storm of factors that led to the opioid epidemic, which continues to claim lives all over the industrial Midwest and Appalachia. It’s made of three strands. The first is a revolution in the medical conception of pain, especially long term, chronic pain, and that it could and should be treated with powerful drugs. The second is the search for a safe drug to meet that need, which eventually led to Oxycontin. The third is slow expansion of a particular kind of heroin distribution operation from a particular small town in Mexico, Xalisco. As the “Xalisco Boys” operation spread into regions not generally thought of as “heroin country” (like West Virginia), they found a fertile ground of addicts already hooked on Oxycontin and looking for a cheaper, better fix.

Each strand has some particularly interesting stories to tell, although they’re not all of equal interest. The retail heroin distribution of the Xalisco Boys is, in fact, quite interesting – unlike the violent drug gangs who sell stepped-on product as a means to enhance the bottom line, the Xalisco Boys competed simply by selling a better product for less money. No violence and a focus on customer service. It makes getting heroin like ordering a pizza – an analogy to which Quinones returns over and over again. That’s the book’s main failing – it treads over the same ground repeatedly, particularly when it comes to the Xalisco Boys.

The other two strands weave together more effortlessly, particularly since they share a common root. In the 1980s a doctor published a “report” – really just a one-paragraph letter to the editor of a medical journal – that his practice hadn’t shown that patient who received powerful pain killers became addicted to them. This became the basis for Oxycontin advertising that opioid medications weren’t addictive, which recent history has shown to be completely false.* In the post-truth era of President Trump and “fake news,” it says something that the basis for Oxycontin’s development and sales was so poorly vetted because there was no profit to be gained in confirming it (because there never was in debunking it).

That’s one interesting linkage between the sellers of Oxycontin and the Xalisco Boys that Quinones hints at, but doesn’t quite make. Both are driven in what they do by the most basic of motives in a capitalist society – not just to make a profit, but to make as much of it as possible. That’s what drove the Xalisco Boys to look for untapped heroin markets. That’s what drove the Oxycontin peddlers to skip past the possibility of addiction and push doctors to prescribe the pills for damned near everything. The bottom line can be damned scary thing.

Dreamland is far from perfect. As stated above, it’s redundant, even beyond the stories of the Xalisco Boys. It’s also pretty dry writing, although it gets the point across. More important, Quinones gives short shrift to the fact that Oxycontin and other powerful pain killers are, for some patients, their only means of dealing with their pain. It also falls into a familiar pattern – of drug dealing bad guys (of various kinds) and good guy cops fighting to stop them – without providing any insight as to whether that’s a battle worth fighting.

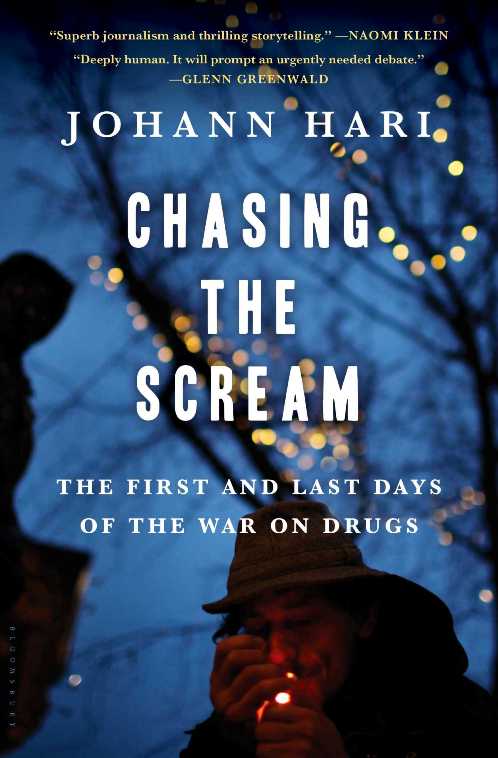

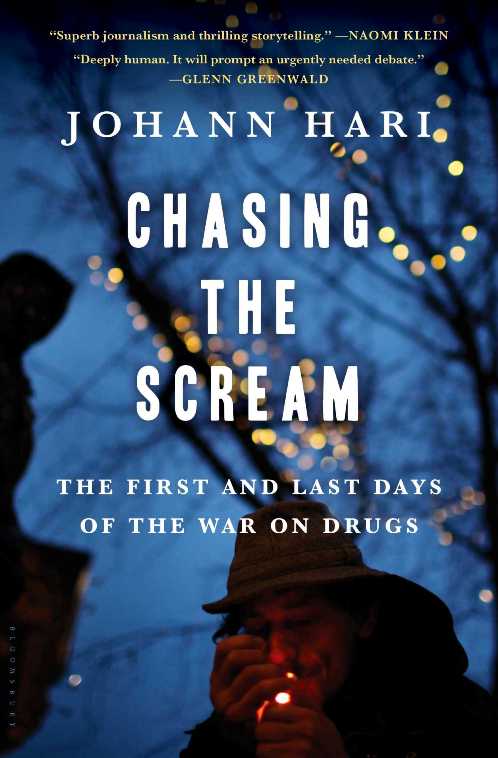

Where Dreamland is a sober telling of an important modern story, Chasing the Scream is a polemic, a call to wake up to the failure of the War on (Some Peoples’) Drugs after more than a century. Dreamland should depress you – Chasing the Scream should piss you off.

Chasing the Scream is journalist Johann Hari’s chronicle of his attempt to figure out how the drug war began and where it’s headed. He travels the world, from his native UK to North America and elsewhere seeking answers about policy, addiction, and alternatives to prohibition. If in the end he doesn’t come up with a singular policy proposal to end the drug war, Hari at least convinces that it’s a war that needs to end (full disclosure – 15+ years of criminal defense practice convinced me of this long ago).

One thing he collects along the way are a cast of rich, memorable characters, from the transgendered former dealer in New York City and the former addict who transformed a particularly seedy portion of Vancouver to an addict who died in prison, cooked alive in the Arizona sun, and a mother whose pursuit of justice for her daughter in Mexico just produced further violence. Most key to the Hari’s book, however, is Harry Anslinger.

Anslinger was the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (the spiritual predecessor to the modern Drug Enforcement Agency) for more than three decades and was, to Hari’s telling, the paradigmatic drug prohibition enforcer. He saw addicts as less than human, used racial and ethnic hatred to stir up panics to grow the power of his office, and was an overall asshole (the “scream” of the title refers to a trauma of Anslinger’s early childhood). Along with jazz great Billie Holiday (one of Anslinger’s high profile targets) and gangster Arnold Rothstein (the prototypical violent drug lord), Anslinger’s ghost hovers over the entire book as the project he started, the War on (Other Peoples’) Drugs expands and is entrenched.

Anslinger is Hari’s antagonist and he spends most of the book looking at the impact of his drug war on those caught up in it and challenging the assumptions underlying it. Of particular importance, he emphasizes the psychological model of addiction over the pharmaceutical model, presenting evidence that most drug users consume their product of choice without much problem, like most people drink alcohol without becoming alcoholics. Along the way he suggests that the scientific literature is clear about the limited addictive power of opioid pain killers, for instance, a claim that Quinones severely undermines.

Compelling as the stories of those caught up in the drug war are, the more interesting bits of Hari’s book are his examination of questions of drug use more generally, and addiction in particular, that shows the entire is more nuanced that Anslinger-style prohibitionists allow. For example, he discusses studies of drug use by non-humans, which is apparently fairly common. Elephants in Vietnam, for instance, generally steered clear of poppy fields until the United States bombing campaign drove them to seek escape from their terror.

It also allows Hari to get into various experiments with alternatives to strict drug prohibition. That includes programs in the UK and elsewhere that allowed addicts to get drugs legally, via prescriptions doled out by a state monopoly. Far from turning into drug fueled free for alls, this allowed addicts to function in everyday society and didn’t lead to more drug use. It also cut off a powerful marketing tool for drug dealers, as the addicts are their best customers. It’s no coincidence that part of the Xalisco Boys scheme that Quinones documents is how they used addicts in a new market to help them advertise and otherwise find customers.

Hari also explores broader legalization and decriminalization programs, such as those in Uruguay and Portugal. Though showing their success, Hari doesn’t dive deeply enough into the Portugal experiment, in particular, for it’s unclear how the law squares legal use and possession of drugs with criminal distribution – the drugs being used have to come from somewhere, after all. More interesting is his examination of the different arguments used by the people backing marijuana legalization in Washington and Colorado in the past few years. The disconnect (WA – drug prohibition is worse that pot being legal, even if it’s bad; CO – pot isn’t bad at all, being less harmful than alcohol) shows that even folks who see the end of the drug war in sight don’t necessarily agree on how to get to that point.

In the end, Hari doubles back to Anslinger for a stinger that brings the rot at the core of the drug war home. The stinger is – Anslinger himself was a drug dealer. He provided for a sitting United State Representative who was an addict to get a safe supply of heroin at a pharmacy (paid for by Anslinger’s agency, no less). The final irony? It was Joseph McCarthy, infamous red scare scam artist. It’s the ultimate example of the hypocrisy that leads me to call the drug war the “War on (Other Peoples’) Drugs,” because it’s rarely about the powerful and connected that are targeted, but the outcast and the hopeless. The war on drugs, ultimately, is a war on them.

Chasing the Scream, as I said, is a call to arms. Unfortunately, Hari may not be the best person to lead the charge, given his prior history with plagiarism and Wikipedia sock puppet scandals. It gives people an instant reason to disagree with anything he says, from snarky internet commenters to book critics (but see, as we lawyers say).

Dreamland is a flawed book, but essential to understanding one of modern American’s great tragedies. Chasing the Scream is the polemic of a flawed messenger about one of mankind’s great modern mistakes. Both are necessary and highly recommended.

* UPDATE: This article from Slate goes into more detail on the one-paragraph phenomenon and how it’s not an uncommon occurrence in scientific journals.