There’s a long-running thread on one of the writers’ forums where I hang out about “books you’ve thrown across the room with force.” The examples are most books that are badly written, not otherwise infuriating. That being the case, if I actually had a copy of Radley Balko’s The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist, rather than the Audible file on my phone, I’d definitely have thrown it across the room a few times while reading it. As it is, I can’t afford the new phone, so I just had to grin and bear it.

From the main title you’d think this book might be one of the nifty mysteries where a pair of mismatched souls find the killer in the end. The subtitle dispels that: “A True Story of Injustice in the American South.” The spine of the book is the story of two men wrongfully convicted of murder in Mississippi and what it took to reclaim their freedom. It’s a story with a pair of clear bad guys, but the lesson of the book is much broader than that.

Said bad guys are the ones mentioned in the title. The “Cadaver King” is Steven Hayne, a medical examiner who at one point was doing 4 out of every 5 autopsies in the state (plus others in Louisiana and some in private cases, too). He did so much work for a couple of reasons. One is that, for decades, the death investigation system in Mississippi was completely fucked up. It was left in the hands of local coroners (elected officials, not necessarily medically trained – the history of the office is fascinating and has little to do with death investigations), who then contracted with actual doctors to do autopsies. The other is that Hayne told prosecutors what they wanted to hear, pushing well past the bounds of what science could say to provide clinching evidence that whatever person the state charged was guilty of the crime.

Bad as Hayne was his sidekick, “Country Dentist” Michael West, was even worse. West started out as the purveyor of a an always sketchy and now debunked field of forensic practice that allowed someone to match bite marks they way others might match fingerprints. With Hayne an expert at finding bites on corpses, even when it made no sense, West could be another link between a suspect and a conviction (why nobody questioned the rise in murders that involved biting is a mystery. As the years went on he developed other skills so that, before his eventually unraveling, he was basically a one-man CSI.

It’s not a spoiler to say that Hayne and West get their comeuppance (West is finally pinned down during a deposition about his magical testimony by an Innocence Project lawyer named – I shit you not – Fabricant) and that two innocent men are freed. But that’s far from a happy ending. There are almost certainly others similarly situated in Mississippi and what makes the book so infuriating is that the entire system is setup to keep them in prison. I’ve had to explain this to clients before – once you’re found guilty, it’s next to impossible to prove otherwise. Finality reigns supreme. The system simply doesn’t care if that might not be the truth and most people don’t want to know (one revealing anecdote is how the Innocence Project at the University of Mississippi got pushback initial because people feared it might suggest some alumni had gotten the wrong people convicted). As Balko puts it in the book, “[w]hat you’re about to read didn’t happen by accident.”

That’s bad enough, of course, but when politics and perverse prosecutorial incentives are thrown into the mix it practically guarantees bad outcomes. That’s mostly because politicians have been so good at weaponizing fear of crime (even as crime rates drop to historic lows) and most prosecutors are elected. You’ll rarely lose an election for being too tough on crime, but go the other way and better start planning for another career. And, as Balko points out, this is a bipartisan problem. When a blue-ribbon federal panel issued a report calling into question large swaths of forensic evidence, the Obama Justice Department dismissed it. Truth is, people rarely care about the details of the criminal justice system unless they or someone they love get caught up in it.

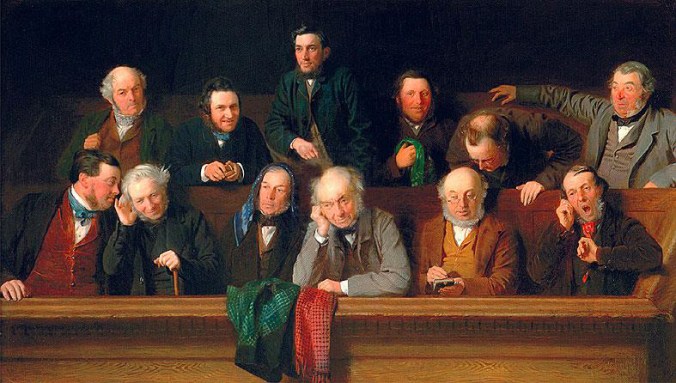

But that only works they way it does because, at bottom, the modern American criminal justice system doesn’t place any priority on determining what actually happened in any particular case. Prosecutors want convictions. Defense attorneys want the best results for their clients, which may be at odds with the actual truth of the situation. Defendants, sometimes facing long potential sentences and no real option of winning in court, plead guilty to things they didn’t do. And, as I said, once that verdict is in, the system is not designed to examine it again.

The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist is a good read. It’s engaging and compelling, frightening and maddening. “If you’re not outraged,” the saying goes, “you haven’t been paying attention.” Pay attention. Read this book.