Remember that list of 10 albums that were particularly important to me I did? It evolved from a Facebook thing. Shortly thereafter, I started seeing other folks do the same for books. Sure enough, one of my friends tagged me and so I had to come up with a list of books (hers was seven, I bumped mine out to ten) that I “love.” Not necessarily meaningful or insightful, just favorites. With that in mind, let’s dive in (in no particular order) . . .

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979)

This is almost a cheat, as the Guide has so many iterations and my favorite will always be the BBC television version (cheepnis and all). Still, I remember pouring through the book (and the other two in the original trilogy) that my brother had. Funny, thoughtful, clever, and an entirely different way to approach science fiction. It stuck to the same part of my brain as Monty Python.

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000)

There are lots of books about writing (some of them actually written by writers!) and people will tell you not to rely on one of them if you’re trying to figure out how to be a writer yourself. As true as that is, the one that everyone seems to recommend is Stephen King’s memoir. For good reason – it’s a brutally honest, open exploration of what it means to be a writer. It doesn’t bury itself in inspirational bullshit, but it also doesn’t make writing seem like something that’s out of anyone’s reach. Reading about writing doesn’t end here, but it probably ought to start here.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)

Since I’m a defense lawyer by trade it’s practically required that I have great reverence for this one. I’d like to say I don’t, that I go against the cliché, but what would be the point? Atticus Finch is, in a lot of respects what lawyers aspire to be, particularly defense lawyers. He seems to resonate particularly with defenders since after a noble and capable defense, he still loses. That’s the life of a defense attorney, after all.

Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance With Death (1969)

I’m not sure whether this was my introduction to Vonnegut (it might have been Galapagos or “Harrison Bergeron”), but it is the one that made me fall hard for his work. The dark humor and deep humanity that runs through his work speaks to me, I guess. Plus, he gave no fucks when it came to style and form – I mean, what kind of book is this anyway? Science fiction? Social commentary? Historical fiction? Who the fuck cares! It’s brilliant.

Candide: or, The Optimist (1759)

I am, at my core, a cynic. On my better days, I’d say I was a realist. Regardless, a bit reason why is Candide, which skewers the idea of this is the best of all possible worlds. Although the story is all about breaking down the titular character’s naiveté, it’s not depressing. It’s darkly comic (there that phrase is again) and liberating, as we see the scales fall from his eyes. While the ending isn’t one you’d call happy, it’s at least hopeful, in that it puts the power for our own happiness in our own hands. Besides, it’s inspired both a fabulous musical/operetta by Bernstein and a concept album by Rush!

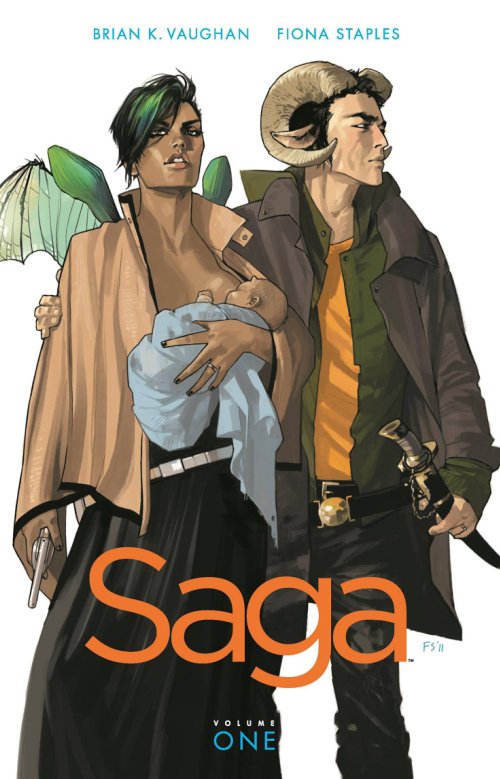

The Private Eye (2015)

Usually when it comes to dystopias the world of the future is completely fucked. Some plague or aliens or nuclear war or whatever has returned life to a primitive state, with characters reduced to hunter gatherers as they try to rebuild society. The dystopia of The Private Eye, by contrast, looks pretty sweet. There’s technology, food is plentiful – it looks like what we think of as “the future.” So what’s the problem? The problem is that everyone stored their data in “the cloud” and one day, “the cloud broke.” From the simple idea that everybody’s data is loose in the world, Bryan K. Vaughn builds a stylish, neo-noir tale for the 21st century. And it looks amazing.

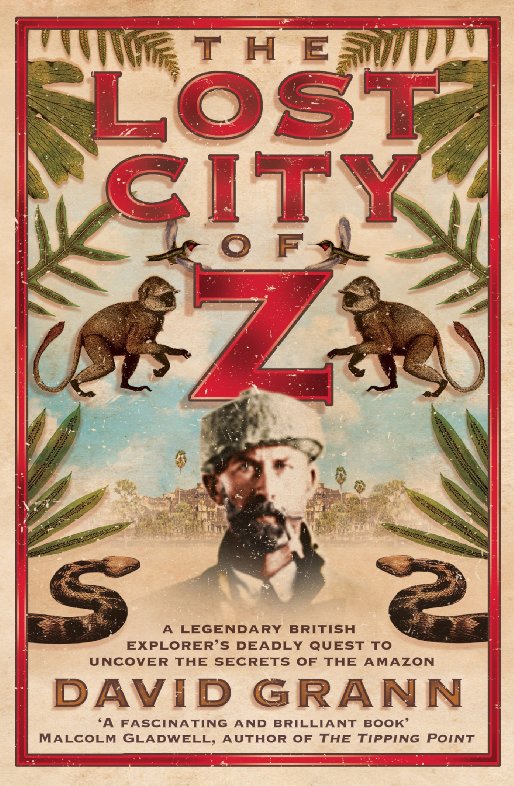

The Devil In the White City (2003)

History is supposed to be dull, a lifeless parade of facts, dates, and names that it can be hard to care much about. It’s not, really (my undergrad degree is in history – trust me!), but that’s the rep. Thankfully, a generation of writers producing “narrative nonfiction” have done a good job bringing the past to life. None is better than Erik Larson and, while all his books are good, this one is my favorite. It’s the story of a grizzly serial killer who uses the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago as cover to lure his victims. That story alone would be good enough, but woven with the story of the fair itself and how it was developed really makes things pop.

Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (2004)

This is a horrible admission for a writer of fantasy, but I’m not a big fan of magic (hence the lack of any in The Water Road). There’s something random and unearned about it lots of times, where the people who wield magic do so by grace of birth or whatnot. What I deeply love about this book is that magic is all about knowledge and, more precisely, books. In fact, the way magic is learned and used in this book makes me think of how law was taught in the pre-modern age, when students apprenticed with members of the bar. Take all that, wrap it up in a magical history of England (and, oh by the way, the Napoleonic Wars), and it makes for an epic read.

Oryx and Crake (2003)

There are many ways of imagining the future. Only Margaret Atwood has come up with one that includes revolting, genetically engineered “chickens” called ChickieNobs:

’This is the latest,’ said Crake.

What they were looking at was a large bulblike object that seemed to be covered with stippled whitish-yellow skin. Out of it came twenty thick fleshy tubes, and at the end of each tube another bulb was growing.

‘What the hell is it?’ said Jimmy.

‘Those are chickens,’ said Crake. “Chicken parts. Just the breasts, on this one. They’ve got ones that specialize in drumsticks too, twelve to a growth unit.

‘But there aren’t any heads…’

‘That’s the head in the middle,’ said the woman. ‘There’s a mouth opening at the top, they dump nutrients in there. No eyes or beak or anything, they don’t need those.’[quote]

That sort of captures the whole feel of this book – at the same time horrible and morbidly funny. It’s a great beginning to a wonderful sci-fi (sorry, Margaret) trilogy.

UPDATE: Eagle eyed readers, or just those with all their digits, will notice I’m one short. Not sure how that happened, since I have the cover and everything, but, alas, I left out one of my absolute all time favorites! Better late, a they say . . .

Good Omens (1990)

Another bit of a cheat, as I get two favorite authors for the price of one – Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. I think this was my first exposure to them on the printed page (I’d come across Gaiman via Babylon 5, of all places) and it melds their styles perfectly. It shouldn’t work, but it does. Hilariously funny and darkly compelling.