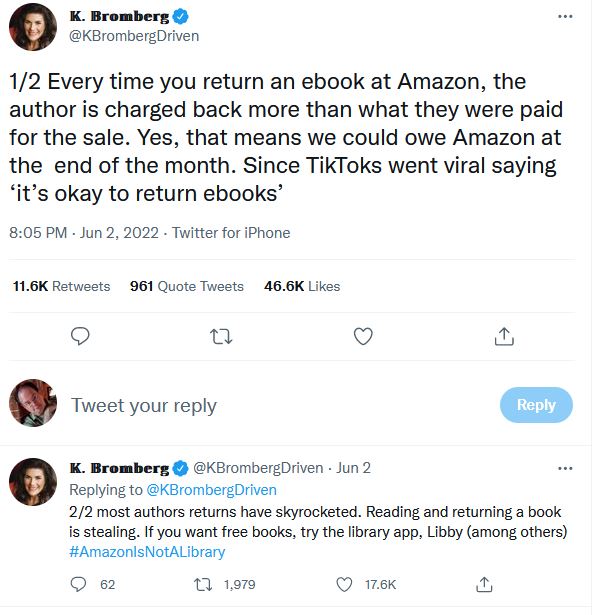

The publishing world (and many many others) erupted last week at the news that the publisher of Roald Dahl’s books, Puffin (the children’s imprint of Penguin Books, naturally) had:

hired sensitivity readers to rewrite chunks of the author’s text to make sure the books “can continue to be enjoyed by all today”, resulting in extensive changes across Dahl’s work.

My only exposure to Dahl’s works is the Gene Wilder version of the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory movie (and the Futurama parody), but my understanding is part of what sets his work apart from other whimsical children’s literature is that it has a bite and nastiness to it that others lack. It seems like what Puffin is up to is smoothing down some of those rough edges to make things more palatable to modern audiences (although how changing the description of Augustus Gloop from “fat” to “enormous” doesn’t seem that different to me).

Predictably, this has been described as “censorship” by some, including Salman Rushdie. Whatever one thinks of this bowdlerization of Dahl’s work it simply isn’t censorship.

For one thing, “censorship” implies the violation of someone’s rights. Whose freedom has been impinged here? Certainly not Dahl, who died in 1990. He hasn’t had anything to say for more than three decades. The only organization with any speech rights in this situation is the publisher or whoever else owns the copyright to Dahl’s works (it’s unclear precisely who is calling the shots after selling rights to Netflix a few years ago). They have the right to say what they want – and refrain from saying what they don’t – even if that might be a dumb move. Unless an author has some perpetual right to have his words reprinted in perpetuity I’m not seeing a violation here.

For another, the key trigger for the term “censorship” should be some type of official action backed by the threatened use of force. That is most likely to come from some governmental body (see the current nonsense in Florida), but could come from a pitchfork-wielding mob, I suppose. Thing is, I haven’t seen anybody demanding that Puffin make the changes that have been made. It appears to have been purely a self-motivated ploy to make more money. It’s capitalism at its finest!

Backing the outrage that there is some stifling of expression going on here is an idea that a writer’s words make their way to the public unchanged by other actors in the publishing process. There may be writers who are big enough to not have to worry about editors, but draft manuscript submitted to an agent or publisher typically goes through lots of revisions before being published. I have ultimate control over my books, since I self publish, but the final product is still shaped by beta readers, the input of other writers, and an editor. I might not take all their advice to heart, but they certainly have shaped the books I’ve released. Hell, Dahl himself made changes in the past to adapt with the times:

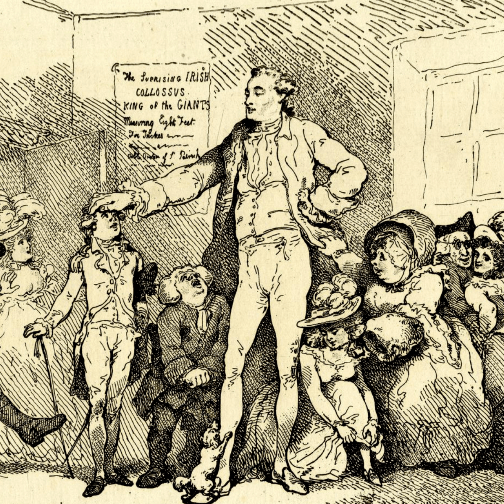

Dahl himself agreed in the late 1960s that his original Oompa Loompas – who in the original 1964 novel were human pygmies bought for cocoa beans in the African jungle – could be recast as the little orange creatures with which we’re all now familiar.

Admittedly it’s different when the author themselves do it, but I’m not seeing censorship here or the violation of anybody’s rights. If anybody has a beef with all this it would seem to be living authors, writing new material for the current world, whose work might be squeezed out:

Philip Pullman reeled off a string of brilliant modern writers who might get read more if Dahl’s texts were left to grow old as their author intended, and thus to drop naturally down the bestseller lists.

Does that mean it’s a good idea for Puffin to try to rewrite what many people consider to be classics? Probably not. As I said, I don’t know Dahl’s work, but this piece at Pajiba seems to get it right:

It does far more damage to pretend that Dahl’s work is spotless, to remove its dark parts and erase from history the very real hurt he caused. The anti-cancel culture people may screech about content warnings, but surely pointing out what’s in a book makes far more sense than cutting it out? This decision had to go through so many people at Puffin. A ton of executives and editors had to sign off on this, to make the decision to participate in the smudging away of reality. Who did they think it would benefit? Dahl himself would have hated it. His readers wouldn’t support it. Schools using his work for classes now have a heap of problems to deal with. They handed a hand grenade of culture war bullshit to the right-wing, and didn’t win themselves any allies on the left. Writers everywhere must now wonder what could be done to their books when they’re not around to say otherwise.

Lurking under all this is the question of why anybody has copyright control of books three decades after the death of their author. The changes here were all made by the current copyright holders, in an attempt to keep the books commercially viable. Without that, anybody could take the old text and sell as many of them as they could. Alternately, of course, anybody could do their own update of Dahl’s stories, albeit without his name on them.

Ultimately, I don’t see this so much as censorship or anything evil, but just a group of people the law allows to continue to make money off a product years after the creator is dead trying to keep the product relevant and marketable. It’s a dumb attempt, but no more than that. Never put down to malice what you can attribute to the simple desire to make more money.

UPDATE: Since I wrote this, the Dahl folks have announced that they’re going to keep publishing the older versions, along with the new rewritten ones. Certainly a whiff of “New Coke” marketing to that. Also, I thought I’d pass along this column about all this which catalogs a great number of literary works that were changed over the years well after their authors were dead. TL,DR, as the kids say – this kind of thing has been happening for a really long time.