Just before I went on hiatus courts in two separate lawsuits by creatives against generative AI companies handed down similar decisions indicating that AI isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. Both concluded that using existing copyright-protected works to train AI engines falls under the doctrine of “fair use.” As one article explained:

The doctrine of fair use allows the use of copyrighted works without the copyright owner’s permission in some circumstances.

Fair use is a key legal defense for the tech companies, and Alsup’s decision is the first to address it in the context of generative AI.

AI companies argue their systems make fair use of copyrighted material to create new, transformative content, and that being forced to pay copyright holders for their work could hamstring the burgeoning AI industry.

Anthropic told the court that it made fair use of the books and that U.S. copyright law “not only allows, but encourages” its AI training because it promotes human creativity. The company said its system copied the books to “study Plaintiffs’ writing, extract uncopyrightable information from it, and use what it learned to create revolutionary technology.”

Copyright owners say that AI companies are unlawfully copying their work to generate competing content that threatens their livelihoods.

Alsup agreed with Anthropic on Monday that its training was “exceedingly transformative.”

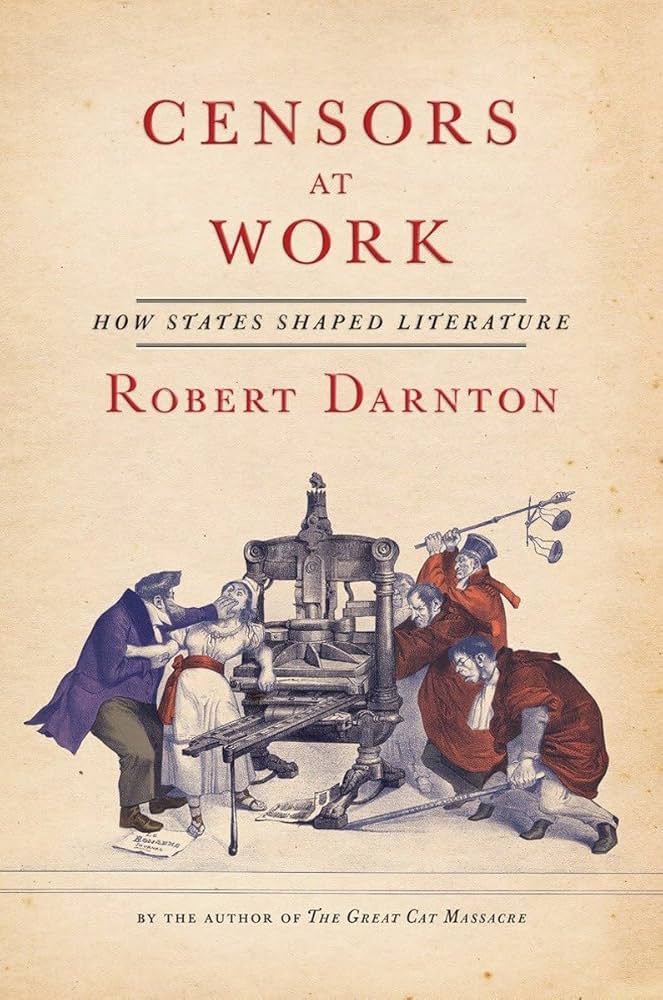

You can read more about the nuances of the various cases here. And this column points out how restrictive copyright can be when a real human being wants to use something that’s currently protected.

While I’m not a party to either suit, I do know that some of my books (likely scraped from pirate sites) are included in at least one collection that’s used for AI training, so I do have some skin in the game. In light of that, I wanted to say a few more words about AI and make some public promises about it.

Part of the trouble we’re having with AI is down to the fact that the law has never really grappled with the nature of computer power in the 21st Century. The pro-AI argument for training on existing works is that it’s the same thing that humans do – all artists and creators are building their own work on whatever they’ve read or seen or heard before. Nobody could seriously argue that a young would-be writer who borrows a bunch of books from friends or families and then writes their own story was fucking with anybody’s copyright. The problem with AI is that it can do that on a massive scale that the law can’t quite fathom.

It’s somewhat similar to what’s happened with criminal records and arrest reports over the past few decades. Those things were always (for the most part) public and accessible to anyone who had the time and desire to go to the courthouse and wade through files to find them. But who actually did, outside of people doing it for a living? Now it’s just a matter of a quick Web search to see if your neighbor was arrested for DUI over the weekend. The law is mostly concerned with the public/private dichotomy, without factoring in accessibility.

Years ago, the Supreme Court was confronted with how to deal with GPS trackers placed on cars and whether they implicated the Fourth Amendment. Generally speaking, to assert a Fourth Amendment violation you have to have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in the place that was searched. By definition, there’s no such expectation when you’re out in public, so there’s never been a problem with the police following people who they suspect of something (but lack the probable cause necessary to arrest them). GPS trackers take that and multiply the amount of data available exponentially in a way that flesh-and-blood cops could never handle. Rather than confront this head-on in the case, the Court took a step back and concluded that the actual placement of the tracker was the problem. We’re still trying to figure out what mass data means when it comes to the Fourth Amendment.

It’s the same with AI and it’s doubtful the law is going to get itself in gear anytime soon. With that said, I have a few promises I’ll make to readers when it comes to AI:

I will not knowingly allow my work to be used for AI training. A good chunk of the AI discourse when it comes to creators is the copyright angle, but even if the AI companies came up with arrangements to compensate creators for the use of their work in training there are still huge issues with generative AI. It’s horrible for the environment. Its products are the worst kind of unimaginative slop. It’s bad for the soul – creativity is a large part of what makes us human and we best not be willing to outsource it to machines. Count me out, regardless of potential reward.

I will not knowingly use generative AI in my writing or music. This should come as no surprise, particularly in light of my NaNoWriMo post linked above, but I won’t knowingly use generative AI in my work. There are other AI variants that are much more common and less problematic (like spell check) that I have always used and will continue to use, but every idea that gets put on a page or in a song is only going to come from my own head – for better or worse! Otherwise, what’s the point?

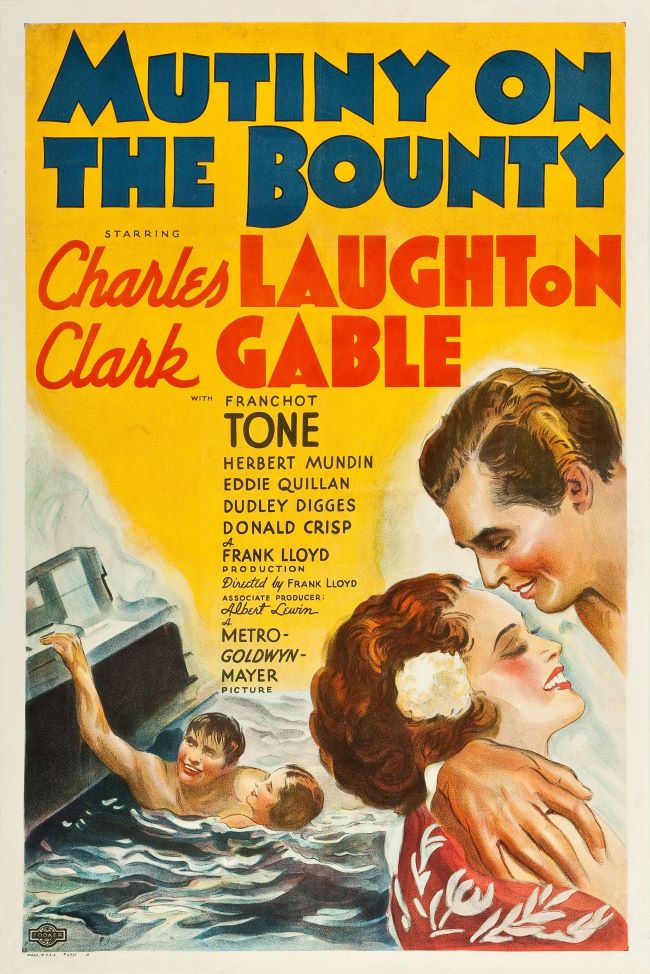

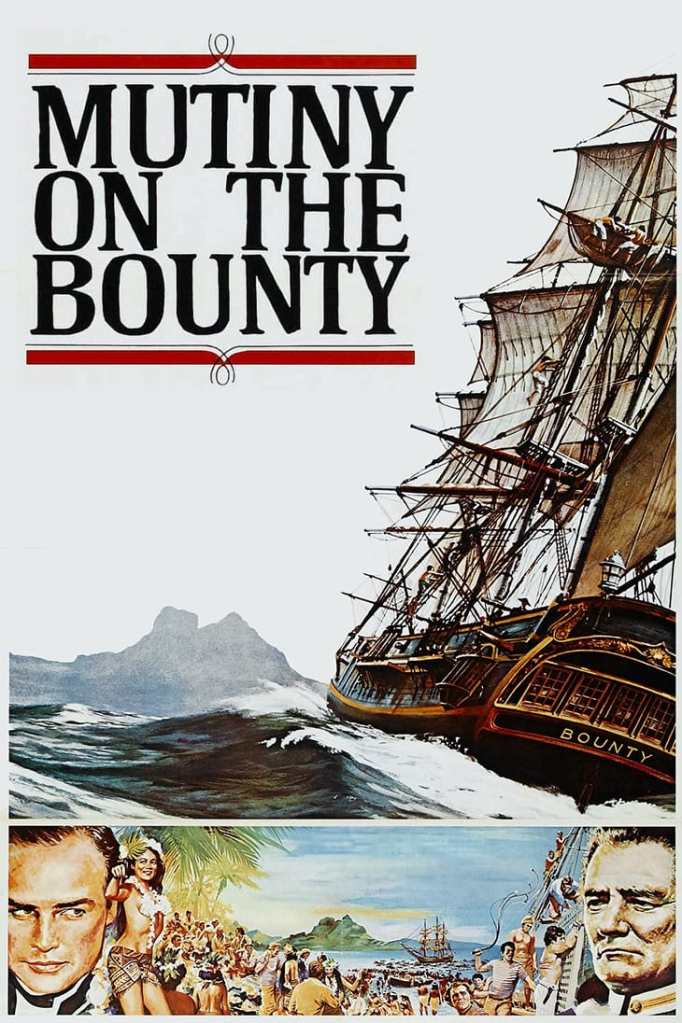

I will not knowingly work with others who use generative AI. I am happy to say that Deranged Doctor Designs, who have done the (current) covers for all my books, are committed to going forward without resorting to generative AI in their work. I will strive to ensure the same with anybody else I work with in the production process.

All this may be pointless, standing on the tracks of “progress” while the train inevitably barrels over me. I may be shouting into the void (I did use to have a blog called Feeding the Silence so it wouldn’t be the first time). As one snappy commenter put it: