It always drives me nuts that when the start of December rolls around (sometimes even earlier!) we begin to see “best of . . .” lists for that year. As if nothing interesting ever happens in December. So, to buck the trend, I wait until January to talk about stuff I found interesting in the year prior. With that said, here’s what most interested me about media – books, music, TV, and movies – last year. Not all of these are 2021 releases, keep in mind. Sometimes I’m a little slow on the uptake.

Books

In term of fiction, the only new-for-2021 book that really stuck with me was The Actual Star, by Monica Byrne (no relation, so far as I’m aware).

The story sprawls out across three separate timelines, each 1000 years apart (basically the far past, the present, and the distant future) and leans more heavily in to fantasy than sci-fi for me, but ultimately the label doesn’t matter. The stories playing out in the three eras tie together really well and there’s a lot of interesting ideas tossed around to chew on. Highly recommended.

In terms of endings, I have to give a shout out to Sex Criminals, by Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky, the comic/graphic novel that wrapped up its run in late 2020 (I didn’t get the sixth and final volume until January of last year).

The series never really reached the heights of the first volume again – the pages (three-and-a-half of them!) where Suzie sings “Fat Bottomed Girls” in a bar, with all the words covered over with exposition explaining how expensive it is to quote song lyrics in a comic – still leaves me rolling. It touched on a lot of interesting things along the way and was never less than interesting. The ending worked, too.

As for things I got caught up on in 2021, a lot of it was historical, not fiction. I’ve recently written about The Invention of Murder and how interesting it was. Another bit of history I really enjoyed digging into was The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom by James R. Green.

It covers the tumultuous history of labor organization in the WV coal fields, generally referred to as the Mine Wars. Very in depth, with lots of necessary background context, but also very readable.

I’d also recommend The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War—A Tragedy in Three Acts by Scott Anderson.

It’s probably the most tragic thing I read last year, given that it tracks how the initial enthusiasm for fighting Communism curdled into dictator-propping-up realpolitk cynicism. Oh well.

Oh, and I read an awful lot about the history of the beautiful game.

Music

2021 was a weird year, musically. Several of my favorite artists – Mogwai, Steven Wilson, St. Vincent, Resistor – released albums last year. All of them are good – I even like Wilson’s electro-pop driven The Future Bites better than most proggers – but none of them really grabbed me. Maybe they’ll grow on me in the future, but for now there wasn’t anything in 2021 really worth taking note of.

As a result, last year was more about getting caught up in some things I’d overlooked – in some cases for a long long time.

Speaking of Steven Wilson, my history with his old (and new again!) band Porcupine Tree is that I preferred the “newer” stuff, from Stupid Dream on, to the older material. The Sky Moves Sideways just feel tedious to me, for instance. But poking around Bandcamp (my happy hunting ground) I found a recent rerelease of the band’s 1996 album, Signify.

That album really hits a sweet spot between the spacier stuff and the tighter, song-driven rock stuff. I also love the recurring samples that mostly touch on religious themes (the guy on “Idiot Prayer” switching from his LSD trip being nearly rapturous to just repeating “please help” does it for me every time).

I’ve given some time over the years to reevaluating music that was popular while I was growing up in the 1980s. Part of that is due to getting into electronic music, including the synthpop of my youth. Part of it is just maturing as a listener to realize that just because something is popular doesn’t mean it’s crap (95% of it is, of course). So when I came across this article written by a professor who used pop culture to open discussions of how people felt during the Cold War I was inspired to go dive into some of the music, including the second Men At Work album, Cargo.

The singles are good and some of the deeper cuts are just as good. “No Sign of Yesterday,” which closes out side one is great. It’s fairly recognizable pop/new wave, but with just enough weirdness to distinguish it.

Finally, another pleasant discovery from Bandcamp was the album Prophecy by Solstice:

Solstice were part of the neo-prog scene of the early 1980s, but with definite folk and Celtic shadings. They only released one album back then, but have released a few more over the years, with Prophecy coming in 2013. It’s great melodic stuff. Wonderful find.

Television/Streaming

You don’t need me to tell you we’re living in the era of peak TV. There’s just so much good stuff out there that I couldn’t touch them all. So let’s focus on pleasant surprises – things that I thought might be decent, but turned out to be really good.

The poster child for this approach is Landscapers.

On the one hand, it’s a true crime story of a married couple who murder the wife’s parents and bury them in the garden then go on the run for fifteen years. On the other, it’s a close study of a couple shut off in their own little world where reality only sometimes intrudes. It’s shot with a grab bag of styles related to classic cinema and includes a bravura scene where the police interrogation room is pulled apart to reveal a set while the scene resets. Brilliant? I’m not sure, but it wasn’t like anything else I saw last year.

I feel somewhat the same about Only Murders In the Building, in that I thought it might have potential, but didn’t think I’d enjoy it as much as I did.

The Martin Short/Steve Martin pairing is as good as ever and Selena Gomez slipped into the mix very well. I’m not sure the actual mystery made much sense, or that I really cared about it, but given the light-hearted nature of things, who cares?

Staged, on the other hand, I was relieved was as good as it was.

I missed the first season in 2020, even though David Tennant and Michael Sheen doing comedy should have drawn me in. That season chronicled their involvement with rehearsals of a play that never actually happened (delayed by COVID and then collapsing). Shot via Zoom (or some similar platform), with their significant others playing themselves it managed to be funny and thoughtful at the same time. The second season, from last year, expands a bit as an American remake is in the works – one which isn’t going to use either one of them as stars (since, apparently, we don’t like them over here). It’s more meta and sillier, but equally good.

Finally, I’m giving a provisional shout out to Yellowjackets.

The first season hasn’t even finished as a write this and it may go way off the rails in coming years (it’s allegedly going to run for five seasons) but so far it’s been engrossing.

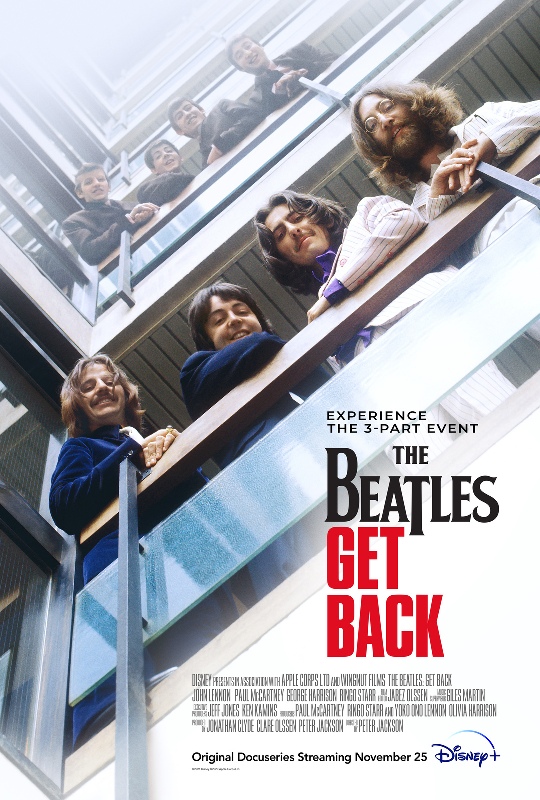

Movies

I can’t say much about movies in 2021 since I didn’t set foot in a movie theater all year (the pandemic and all). I watched a few 2021 releases on streaming services, but nothing that really wowed me. As a result, I think the “movie” that stuck with me most from the year was Get Back, Peter Jackson’s epic excavation of The Beatles. I already wrote about that here.

That’s it – on to the new year!