I’m a child of the 1980s. By the time Ronald Reagan took office I was old enough to be aware of the wider world. That included the Cold War and the fact that there was a looming threat of nuclear annihilation hanging over our heads. That’s a lot to handle for a ten-year old.

Thankfully, I had my (decade) older brother, Todd, to put it in perspective. He assured me there was no point in worrying because there was nothing we could do about it, anyway. Beyond that, where I grew up in South Charleston, West Virginia, was a hotbed of the chemical industry and was likely a first-strike target. If the Soviets loosed the dogs of war, my brother said, we’d be vaporized in an instant, with no pain or worry about how to survive.

Once the Berlin Wall came down and the Soviet Union fell apart the specter of superpower-led nuclear annihilation faded in the face of terror attacks and climate change. But the potential for nuclear apocalypse is still with us and fiction (in its various forms) is still trying to deal with it. What’s so utterly fascinating – or depressing – is how similarly the topic has been treated over the years.

I fell down this rabbit hole last fall, starting when I saw A House of Dynamite, the latest film from Kathryn Bigelow.

It’s about a sudden, unexpected launch of an ICBM from the Pacific which, initially, everyone figures is just another test that will eventually fall into the ocean. It doesn’t take long, however, for the math to show that it’s headed for the Midwest and, more specifically, Chicago. Over the course of three 17-minute loops we see people on various levels trying to deal. An attempted shootdown fails, leaving the president with a decision about retaliation. But against who? And how much?

Watching A House of Dynamite brings out some sickening déjà vu if you’ve consumed almost any nuclear fiction in the past. Inevitably, we hurtle toward the only response that ever seems to be an option – full retaliation, because if we don’t we might not get a chance to do it later (and the American people, what’s left of the, wouldn’t tolerate that).

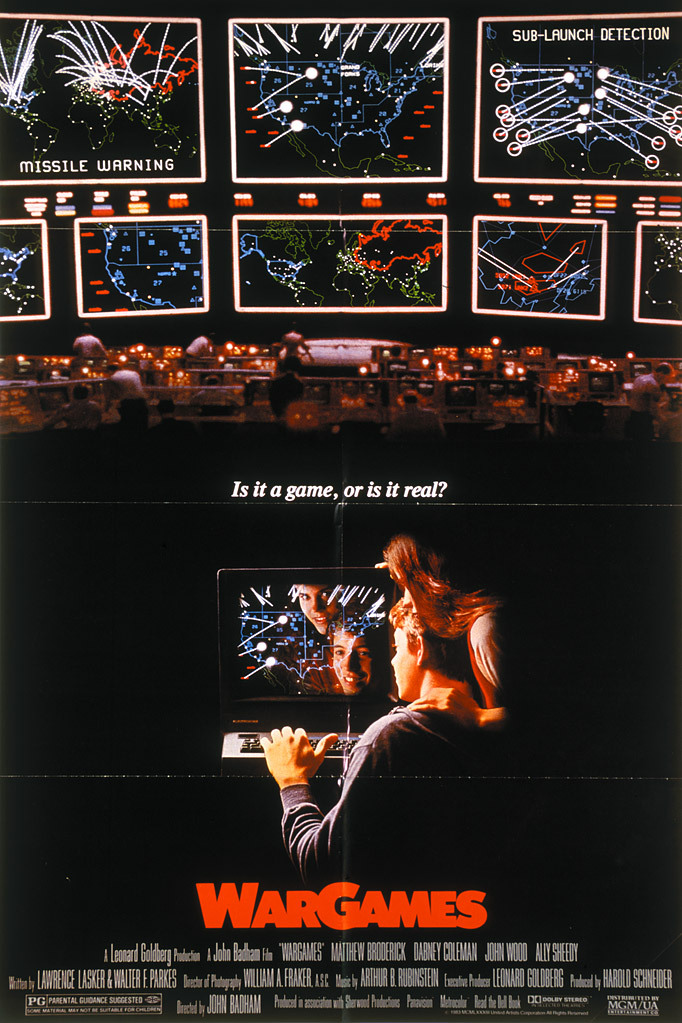

A House of Dynamite feels like it’s in conversation with some earlier movies, even if only subconsciously. The one that immediately sprang to mine for me, and which I rewatched immediately afterward, was 1983’s WarGames.

The first loop in A House of Dynamite takes place in the White House situation room, which has a wall full of monitors displaying data. The pivotal scene in WarGames takes place deep inside the mountain headquarters of NORAD, which has an even more immense wall of monitors.

Our characters are all locked in there because the computer that controls the United States’ nuclear arsenal (installed after actual humans failed to launch missiles during an exercise) tries to launch a retaliation for a Soviet attack that is, in fact, just a simulation. In order to teach the computer the error of its ways, it’s forced to play Tic-Tac-Toe against itself to discover the concept of futility. Then it switches to running through scenario after scenario for nuclear war, all of which lead to the same end – complete destruction. Disaster is averted when the computer, famously, realizes:

The tie in with A House of Dynamite, for me, is that regardless of which “variant” the computer entertains – from all-out initial attack to “minor” exchanges by smaller countries – the result is the same: everybody throws everything they have at each other. There is, it appears, only one end point to any nuclear exchange.

In that sense, the other movie I immediately thought of, Fail Safe, actually has a happy ending!

I actually read the 1962 book Fail-Safe before rewatching the 1964 movie and, I have to say, this is one of those situations where the movie greatly improves on the book. Fail-Safe, like many of these movies and books, has a great ticking clock creating dramatic tension. The book wastes too much time getting there, while the movie is much more efficient.

“There,” in this case, is a mistake involving “fail-safe points” used by the United States Air Force. American bombers would fly toward those points, waiting for a recall notice that would turn them around. Without the notice, they go on to hit their targets in the Soviet Union. Most importantly, they ignore any attempts to turn them around. Due to some kind of glitch (the book and movie differ on precisely what) one squadron doesn’t get the recall notice and heads for Moscow.

What follows is a very tense unravelling of expected behavior. Trying to stave off starting a nuclear war, the Americans help the Soviets try to shoot down the bombers, but one still makes it through. Meanwhile, a debate rages in the United States about what to make of all this and whether it could be an opportunity to strike the Soviets for real (a theory pushed in the movie by . . . Walter Matthau?!). In the end, the president comes up with a horrible bargain – once the American bombers hit Moscow, another American bomber will drop the same bombs on New York City. An eye for an eye, essentially. The movie ends in pretty chilling fashion.

But, as I said, this is actually a happy ending! Rather than falling into complete catastrophe, the higher ups in the United States and Soviet Union manage to at least limit the damage and prevent an all-out nuclear war. Regardless, the message of the book and movie are clear – we don’t have a good grasp on nuclear weapons and how they might get used by mistake and what that means for the world. I’ll add that the attempt by some to avoid responsibility for all this by blaming the machines sounds very loudly in the modern AI-besotted world.

Compare that to, say, 1964’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, which shares a lot of plot scaffolding with Fail Safe (to the point there was litigation about it). Strangelove offers no hope whatsoever – not only is there nothing you, personally, can do to stop a nuclear apocalypse, the people that could do something are venal idiots that are likely to fuck things up in the end. In Strangelove’s world the only thing left to do is laugh (and crank up the Vera Lynn – anybody remember her?).

What all these works share, however, is a focus primarily on those people making the decisions. A House of Dynamite’s three loops work steadily up the chain, from information gatherers to experts to political end decision makers, but these are all still people whose jobs are to deal with the possibility of nuclear war. Given that I’m not sure what it says that, in all of them, the nuclear wars never start (or almost start) on purpose. It’s always an accident or someone else’s fault. As Men At Work sang, it’s a mistake.

That’s not the case when the focus is on regular folks dealing with the impact of a nuclear attack.

Growing up, the most famous version of that story was The Day After a 1983 made-for-TV movie (directed by Nicholas Meyer, fresh off Wrath of Kahn) that depicted a nuclear attack on the United State through the eyes of regular folks in Kansas and Missouri (what’s the hard on for nuking the American Midwest?). I don’t remember the actual movie itself, but I do remember the fallout (so to speak) from its broadcast. It hit pretty hard, even getting to Reagan.

Years later, I heard about the “British version” of that movie, called Threads. It has an epic reputation that’s on par with Magma albums or aggressive art installations. I figured this was a good time to check it out.

Threads stands in Sheffield for the American Midwest, but more importantly it depicts a population that has no plausible connection to their fate. The Americans in The Day After, theoretically, had a say in who ran the country and built up the nuclear arsenal that was unleashed. A strong theme of Threads is that the citizens of Sheffield were likely to be atomized in a conflict in which they had no part to play, aside from radioactive cannon fodder.

For that reason it’s, truthfully, the first third or so of Threads that really worked best for me. The way it portrays society starting to fray at the mere possibility of the bombs dropping (we learn, entirely from news reports, that the Soviets invaded Iran and the United States is pushing back) is entirely too realistic. Police crack down on protestors, some people just don’t want to think about it, others are obsessed. It feels very real and human. The stuff after the bombs drop, by contrast, is horrifying and depressing but also completely one note. There’s no humanity left in the aftermath, which might be realistic but feels too pessimistic even for my cynical heart. That said, had to have a lot of puppy therapy after Threads.

Even worse, maybe, in its own way, was On the Beach.

I read the 1957 book by Nevil Shute, forsaking the movie version starring (among others) Gregory Peck and Fred Astaire, which just doesn’t seem like his kind of movie. Set in Australia, it’s the story of several people – all connected to a US naval officer and his Australian liaison – riding out a nuclear exchange and waiting for the fallout to slide far enough south that it kills them. As in some of the WarGames scenarios that flash on the screen, this war started small but bloomed into a world-engulfing conflagration. But, as with Threads, it had little if anything to do with the Australians who make up most of the cast.

The driving force of On the Beach is fatalism. This is a story of people who are waiting to die, not trying to figure out how to survive what’s coming. Nobody mentions a shelter, nobody works on how to live with fallout. The most you get is a futile submarine voyage that confirms that everybody else on the planet is dead.

And everybody is fairly stoic about it. There are various forms of denial, sure, but nobody decides to go indulge in any horrific or taboo conduct now that the end of days are on the horizon. One character (the one played by Astaire in the movie) manages to get his hands on a Ferrari F1 car and enters it in the most ghoulish motor race ever put to the page (makes 1955 at Le Mans seem tame), but that’s about it. Mostly, everybody kills themselves once the fallout starts to settle in.

So, yeah, not the most uplifting of reads. But I think it definitely captured a feeling of the time, one that people probably didn’t want to think about too much.

To round things up, a shoutout to a recent American Experience documentary, Bombshell.

Not fiction, but about fiction – specifically, the propaganda efforts around the development and deployment of the atomic bombs against Japan. Covering only up to about 1948, it shows how even from the dawn of the nuclear age there have been stories told about it, outright fictions (largely, attempting to cover up the effects of fallout after the bombing of Japan). There’s always a narrative, somewhere, that somebody has to sell.

Where does that leave us in 2026? Fuck if I know. What nuclear fiction has taught me is that we’re likely to blunder into something awful and be unable to contain it. And that for all the decades we’ve lived with these weapons, we still don’t really know what to do with them. Which is terrifying. In which case, we’re right back where I was in the 1980s listening to my brother – ain’t nothing we can really do about it and hope one hits nearby and puts us out of our misery.

I’m currently reading The Long Tomorrow by Leigh Brackett (who wrote the first draft of Empire Strikes Back), a post-nuclear-apocalyptic book in which cities are outlawed and almost everyone has become a Mennonite after nuclear destruction since they’re the only ones who knew how to survive on their own

>

LikeLike

Reminds me a little of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Canticle_for_Leibowitz

LikeLike