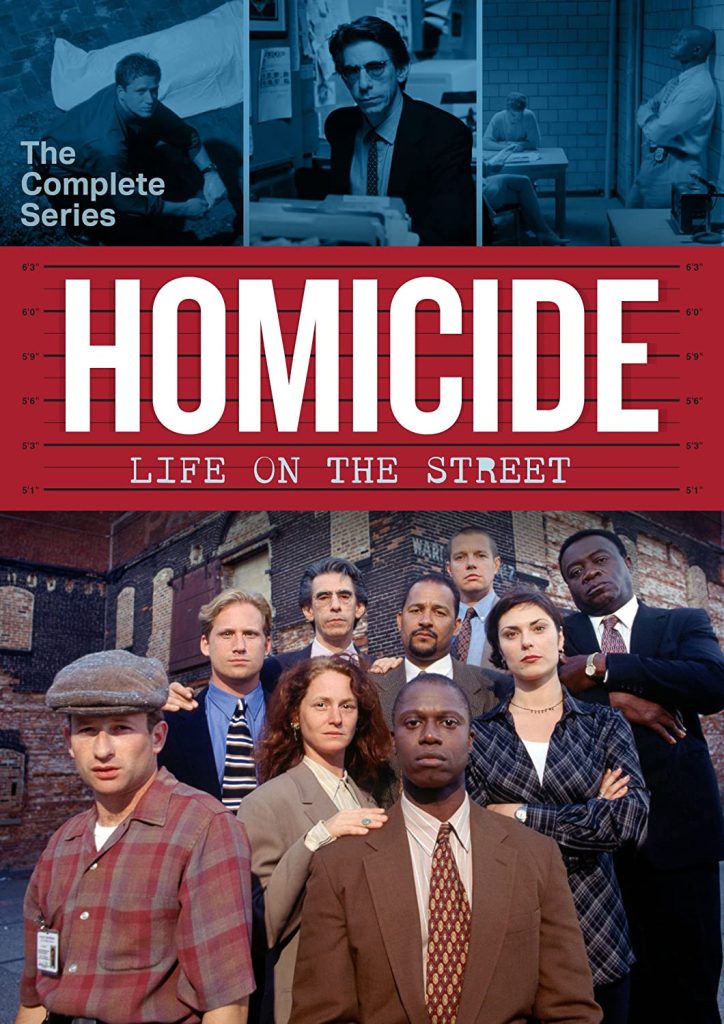

Last fall one of the great injustices of the streaming world was remedied when the entire run of Homicide: Life on the Street (including the wrap up TV movie) was finally available to stream on Peacock.

Yes, some of the music cues had to be changed due to rights issues (miss my “No Self Control” drop!), but otherwise the show looks and sounds better than it has for years. Created by Paul Attanasio (with an assist from director and Balimore guru Barry Levinson) and based on a book by then-journalist David Simon called Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, the show broke a lot of ground for network TV and helped usher in the cable shows we now think of as peak TV, including Simon’s The Wire.

I wish I could say I was into Homicide from the jump, but the truth is I only remember being able to drop in here and there during the show’s original run. I liked what I saw, but it was harder to watch a specific show back in those days, kids (it was on Friday night for part of its run, for fuck’s sake!). Where I really picked up the show was on cable a few years later and, ultimately, by getting the entire series on DVD. In spite of having it right there, I hadn’t really watched it for years until it hit Peacock last year.

The relaunch on streaming led to a good deal of reportage on Homicide’s place in the TV pantheon, which caught my wife’s attention. She’d not seen much of the show, but decided it was worth diving in in light of the hype. How does the series hold up during a full-length rewatch after all these years?

Dramatically, Homicide holds up remarkably well. Part of that is due to the fact that it doesn’t look or feel like a product of 1990s network TV. If you listen to the (hopefully not gone for goode) podcast Homicide: Life on Repeat, Kyle Secor and Reed Diamond talk a lot about how differently the show was shot and other technical things that are, mostly, above my head. Still, it doesn’t feel like a TV show from thirty years ago, from an era with commercial breaks and network censors looking over everyone’s shoulders.

That extends to the storytelling itself, of course. The cops of Homicide are not (generally speaking) heroes out there braving the mean streets to make the world safe for democracy. They’re just men (mostly) and women trying to do a job and get through days filled with horror, pain, and uncooperative witnesses. Cases frequently remain unsolved (the “board” – a large dry-erase board that lurks to one side of the squadroom tracking open and closed cases – is practically a character itself). Unlike it’s NBC stablemate Law & Order things rarely go to court, so most often it’s the arrest, the clearance of the case, that matters, not ultimately whether justice is actually done. Homicide depicts police work as a grind, as a kind of assembly line, rather than a great, noble calling. It’s not unlike the practice of law, in my experience.

None of that would work without amazing work from the cast, both the series regulars and guests (again, like Law & Order, there are lots of “hey, they went on to . . .” moments). Secor, as Tim Bayliss, provides the perfect audience surrogate, the new guy to the squad who has to figure out the rhythms of the work and whether he should really be there are all. Andre Braugher rules as Frank Pembleton, master of “the box,” and the last person you want to sit down with for a chat. That the series doesn’t shy away from the fact that interrogations are often about tricking idiots into incriminating themselves adds a sleazy sheen to proceedings.

I’ve already mentioned Law & Order a couple of times and it’s impossible not to compare the two shows. I’m no Law & Order hater, in spite of my profession, but that show does seem to have a more upbeat attitude toward police work than Homicide does. A great example of that is two stories that dealt with suspects who really looked guilty, but the facts didn’t show it.

On Homicide, Bayliss’ first case as a primary is the sexual assault and death of a young girl, Adena Watson. Through most of the first season he and Pembleton try to build a case against a neighborhood fruit seller who really appears to be the best suspect, but they can never actually pin the murder on him. An entire episode is devoted to his interrogation, after which nothing has changed. The case remains unsolved (as did the real life inspiration in Simon’s book) and haunts Bayliss through the rest of the series. Viewers are left without any real closure, either.

Compare that to the Law & Order episode “Mad Dog” from 1997, in which a rapist prosecutor Jack McCoy had convicted years prior is released on parole, over McCoy’s furious objection. Shortly thereafter, there is a rape/murder in the neighborhood that bears the released guy’s modus operandi, but no real evidence to connect him. Detectives and prosecutors spend most of the episode deploying various tools of surveillance and coercion to trip the guy up, to no avail (McCoy is even chided by his boss for “dragging the law through the gutter to catch a rat”). It could have ended like that, with a sense of unknowing and asking serious questions about police conduct. Instead, a second assault is interrupted by the would-be victim taking a baseball bat to the skull of her attacker – who is, of course, the recently paroled rapist. In a flash we get closure and knowledge that not only had the cops and prosecutors been right all along, but that the bad guys’s dead, to boot.

All of this leads to an interesting question rewatching Homicide after all these years – is it copaganda? That is, do the stories it tells valorize police in a way that polishes their public image in a manner that can lead to the public letting police get away with stuff they never should get away with? Although it’s hardly a new phenomenon, I don’t remember “copaganda” being a term back during the show’s original run or it being discussed as such. There are certainly moments when the show leans that way – for all their faults, the cops are still fairly noble and have a sense of purpose as “murder police” (as Meldrick Lewis would put it), but overall it doesn’t really feel like it. These cops cut corners, unashamedly treat some murders as more worthy of solving than others, and worry about bulking up overtime. It’s not pure copaganda, at any rate, which makes sense given the issues many of the characters’ real-world analogues have had.

But I might be biased. For all the glory heaped upon The Wire, which is great, I always held Homicide in higher esteem. It seemed to get there first, but did it with constraints that would strangle a modern “prestige TV” series. After rewatching I still do. It’s an amazing achievement and, if you’ve not seen it, you owe yourself some binging.

I loved Homicide back in the day. I was pumped when it finally joined the streaming world. I enjoyed hearing your thoughts. I wish I had a more profound comment but that’s it.

LikeLike