Sometimes I fall down rabbit holes. This particular one I’m going to blame on Turner Classic Movies.

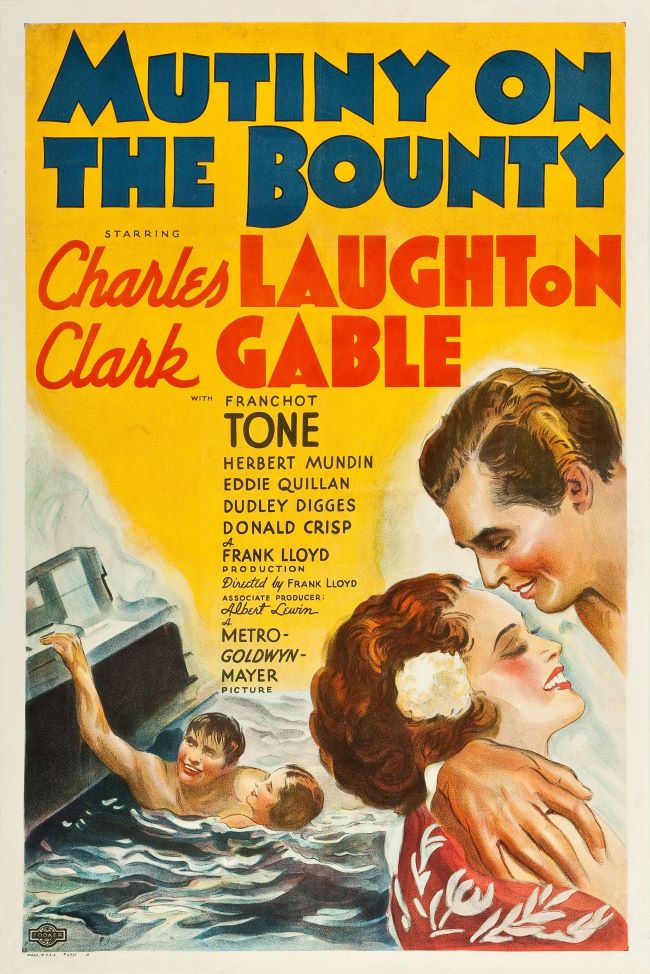

As I think I’ve said before, part of my work morning routine is to flip through the schedule on TCM to see if there’s anything worth recording that day. Months ago I found such a thing, the 1935 version of Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Laughton and Clark Gable.

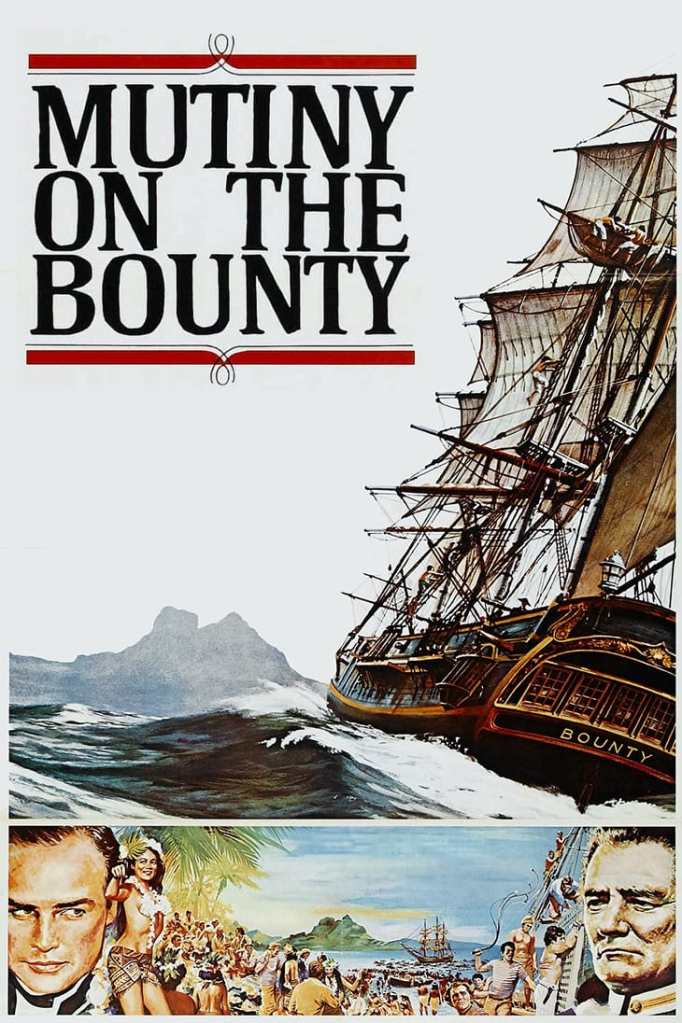

Having never seen it, or any other Bounty story, I recorded it. It sat on the TiVo long enough that TCM also showed the 1962 version (with Marlon Brando), so I recorded that as well.

When my wife saw both sitting there, she wondered aloud about if I intended to watch the 1984 version, Bounty, with Mel Gibson and Anthony Hopkins (and Daniel Day Lewis and Liam Neeson!).

So, one Saturday, we did the deep dive and watched all three back-to-back-to-back. And then I read Caroline Alexander’s The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty to actually get the history of the whole thing.

Watching different versions of the same story, the history of which is not as clear as you might think, made for some interesting comparisons.

But first, the basic history – in 1787 Bounty left England, under the command of William Bligh, for a journey to Tahiti. There, the crew would harvest breadfruit plants for transport to Jamaica, where it was hoped they could be replanted and used as a cheap food for the enslaved population. Sometime after Bounty left Tahiti one of Bligh’s underlings, Fletcher Christian, led a mutiny. Bligh and several loyal men were put adrift in a launch (and managed to make it back to civilization), while Christian and the others found their way to Pitcairn Island, where their descendants live to this day.

What’s particularly interesting about the history (from Alexander’s book, at least) is that there is a gaping hole in the record when it comes to Christian. Bligh, the men in the launch, and even some of the other mutineers returned to England where there were various inquiries into the mutiny, but Christian never did, dying (or being murdered) on Pitcairn. His precise motivation for the mutiny is unknown, therefore, and leaves a lot of room for fictional variation in the story.

For example, the portrayals of Bligh vary considerably between the three movies. As played by Laughton in 1935, Bligh is a tough-love legal enforcer. The law of the sea is harsh and brutal, but it’s necessary to keep discipline on what is a very dangerous voyage. The 1962 Bligh, by contrast (played by Trevor Howard), appears to get off on the punishment he dishes out (which Christian calls him out for). He may use the legalish language that Laughton did, but it appears to be a cover for more personal motives. Hopkins in Bounty, on the other hand, dishes out much less discipline (particularly before the reach Tahiti), but seems much more paranoid about possible plots. Per Alexander’s book, Bounty was probably the closest to correct, as Bligh didn’t appear to be any firmer of a disciplinarian than the normal English captain of the time. That said, Bligh also suffered a rebellion (land mutiny?) when he was a territorial governor in Australia later in life, so clearly there was something about his leadership style that rubbed some people the wrong way.

The same is true for Christian, whose motives shift from telling to telling. Gable’s version, perhaps polished to match his matinee idol status, was driven to mutiny on behalf of the lowly sailors who Bligh abused. Notably, that version of Christian had served with Bligh before and had some idea that there might be trouble. It’s a pretty simple narrative. The 1962 version Brando played takes longer to get to the same place and, when he does so, simply snaps, rather than more coolly plots the mutiny. This Christian didn’t know Bligh before, so he’s perhaps more shocked by the brutality. Where Brando’s Christian really differs from Gable’s is the weight that command puts on him after the mutiny. Gibson’s version is motivated less by Bligh’s cruelty (since there’s less of it) than his affection for life on Tahiti. He appears, to quote Londo Molari, to have “gone native” and is willing to do whatever it takes to get back. This Christian didn’t just know Bligh prior to being on Bounty but was good friends with him, which again kind of pushes the cruelty angle to the side. Which of these is closest to truth, if any, is anybody’s guess.

The movies differ considerably in what happens after the mutiny, too. In the 1935 version, after Bligh makes it back to England, he is exonerated of anything to do with the mutiny, then heads off back to the South Pacific (true!) where he tracks down Christian on Tahiti and forces him to book it to Pitcairn (false!). Post-mutiny life for Christian is pretty swell, as least until Bligh shows up. In the 1962 version, Bligh is again acquitted, but with some comments from the judges afterwards that maybe he had it coming, anyway. There’s no return voyage. For Christian, as I said, command weighs heavily on him so much so that on Pitcairn he floats the idea of returning to England to tell their story. This prompts others to burn Bounty in the bay and Christian dies trying to save it (ending courtesy of Billy Wilder, rather than any historical basis). The 1984 version gives Bligh a full exoneration, while making Christian’s life after the mutiny even more miserable. The landing on Pitcairn comes off less of a triumph and more pathetic than anything else.

What none of the movies really do is dig into what happened in England once Bligh returned. There really was a court martial at which many of the mutineers (returned from Tahiti by other vessels) were convicted of mutiny, although many were acquitted (including a potential ancestor of mine!). Several were sentenced to hang, but two were pardoned. News coverage of the court martial was largely favorable to Bligh, but Alexander chronicles how that shifted over the years, thanks in part to Christian’s family and some of the other sailors involved. It’s safe to say that the popular conception of Bligh, closer to Laughton’s and Howard’s portrayals than to Hopkins’, is largely due to their out-of-court efforts.

Particularly interesting in the variations is that the 1935 and 1952 movies are both based on the same set of novels, so you’d think they’d be more similar. They’re both big screen spectacles and the 1952 version was no doubt made just to take advantage of color, but they are quite different in the people whose stories they are telling. I think I prefer the 1935 one. Laughton’s Bligh may be the farthest from the truth, but he’s pretty compelling and in his devotion to rules without empathy scarier to me than Howard’s psycho Bligh (remember, I’m a public defender by day). While I appreciate the ambiguity of the 1984 film, it doesn’t resonate quite as much (in spite of the Vangelis score).

Usually when a movie is made about a historical event the discourse breaks down into whether the movie got it “right” or how “wrong” it actually got things. The whole Bounty situation is a good example of how history isn’t so obvious in lots of situations and lends itself to different interpretations. Surely there’s another Bounty movie or TV series in the works that’ll provide an entirely different perspective, too.

Who is the potential ancestor?

LikeLike