Dystopian fiction can be tricky. Assuming you’re setting it on Earth, you either need to have the whole world go to hell, which isn’t all that probable, or the shit show is more localized, in which case you have to address how the rest of the world interacts with the place where the story is set. I’ve been set to thinking about this a bit thanks to two recent bits of television.

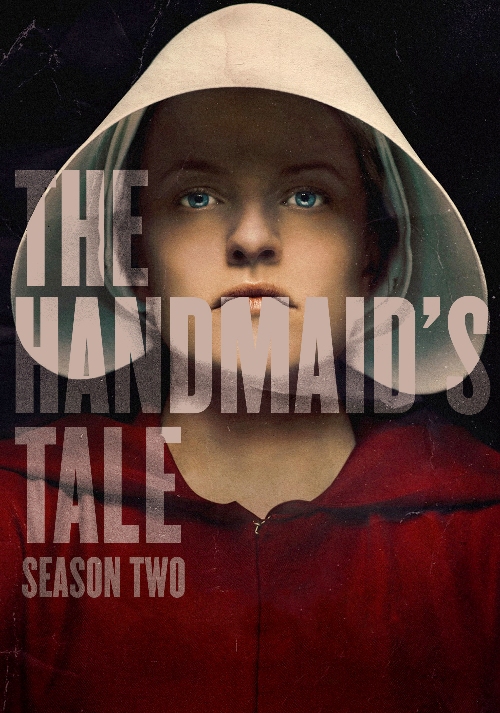

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is as localized as dystopia can get. It’s told entirely from the point of view of the titular handmaid, June, and doesn’t concern itself at all with the outside world. Gilead is what she experiences; nothing more.

The TV adaptation probably couldn’t have worked if it maintained that rigorous POV, so it wisely broadened its world from the get go. In the first season, therefore, we learned that June’s husband and her best friend managed to escape to Canada, where there’s a growing population of expats from the area that used to be New England. But we don’t really know what that means in a global socio-political sense.

That was evident in the recent episode “Smart Power,” where Commander Fred and his wife, Serena, take a diplomatic trip to the Great White North. They’re received professionally, if coolly, in the manner you’d expect for delegates from a nation with which the Canadians have at least some normal relations. But do they? We don’t really know. Things are complicated when an American agents of some kind offers Serena a new life in Hawaii, one where she actually gets to control her destiny.

All this is a bit confused because we don’t really know how Gilead relates to the rest of the world – or what the rest of the world thinks of Gilead (once some info leaks out during the Commander’s visit, we quickly find out, at least partly). How big is Gilead? We know it’s centered in New England, but what of the rest of the United States? Does Canada recognize it as an independent nation? If so, why? What does the United States look like?

None of these were really important in the book, since it was June’s story above all else. But by broadening the focus (something that had to happen for the TV series to continue), these questions become relevant and I’m not certain the show’s brain trust really has the answers.

The recent HBO adaptation of Farhernheit 451 suffered even more acutely from this problem. It makes explicit the story’s setting (Cleveland) and, via an implausible update that involves the works of humanity encoded into DNA, sets up an endgame where Montag has to help someone escape to Canada to rendezvous with some scientists. We’re never told if that’s just because that’s where they are or because Canada is the safe area we always assume it to be.

This is particularly important to Farhernheit 451 given its semi-hopeful ending of an underground group dedicated to actually memorizing great works of literature to ensure they don’t disappear.* That still happens, but it’s now supplemented with the DNA thing. But if Canada is a safe haven, if it exists outside of the dystopia the United States has become – then why the need to preserve all knowledge? Isn’t it safe elsewhere in the world?

To a certain extent this is an issue with any speculative fiction worldbuilding. Writers need to have some idea what happens beyond the bounds of their stories, since those things should influence those stories in some ways. But it’s compounded dystopian fiction set in the “real” world because readers and viewers presume the world is as it is in real life, unless we’re told otherwise. That can lead to confusion, or at least some disappointments.

* Kudos to the writers for updating the preserved works to include writers who are women and people of color (and even some women of color!). However, the impact is a bit muted since only the minority characters are memorizing the work of minority authors.