I’ve got a fondness for micronations, those tiny bits of land that someone has declared a small, independent nation that nobody else in the world really recognizes (aside from other micronations). My favorite, up to this point, has been the Principality of Sealand, which is actually an old offshore platform in the North Sea off the British coast.

Sealand even has its own soccer team (there’s an entire World Cup for unrecognized nations) and, I’m pretty sure, inspired an excellent song by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark Song:

That’s interesting and quirky and all, but is a micronation art? It certainly can be.

Welcome to the Republic of Zaquistan:

You might think it’s just a few acres of scrub in the Utah wilderness (and you wouldn’t be wrong), but it’s also a project of artist Zaq Landsberg. I found out about him via this article in the Washington Post about his statue “Reclining Liberty,” currently installed in Arlington, Virginia, in which he translates the Statue of Liberty into the form of the reclining Buddha you can find all over Southeast Asia.

I like the whole vibe of it:

one of the piece’s goals is to be accessible — Lady Liberty is relaxed in the grass, not towering above viewers from a pedestal. It is easy to interact with her, and he hopes that people will.

‘There’s plaster layers, the copper, the patina, but really, the last layer is the kids climbing on it,’ he said. ‘This thing, it’s on the ground, there’s no pedestal, there’s no admission ticket, there’s no velvet rope.’

So something like Zaquistan is right up his alley. He’s filled the scrub with various sculptures and installations, including a “port of entry” and Victory Arch. My favorite, though, are The Guardians of Zaquistan, a couple of large 1950s-style robots. According to the place’s website they were installed in 2006 and “[t]o this day they steadfastly protect Zaquistan’s borders from intruders.”

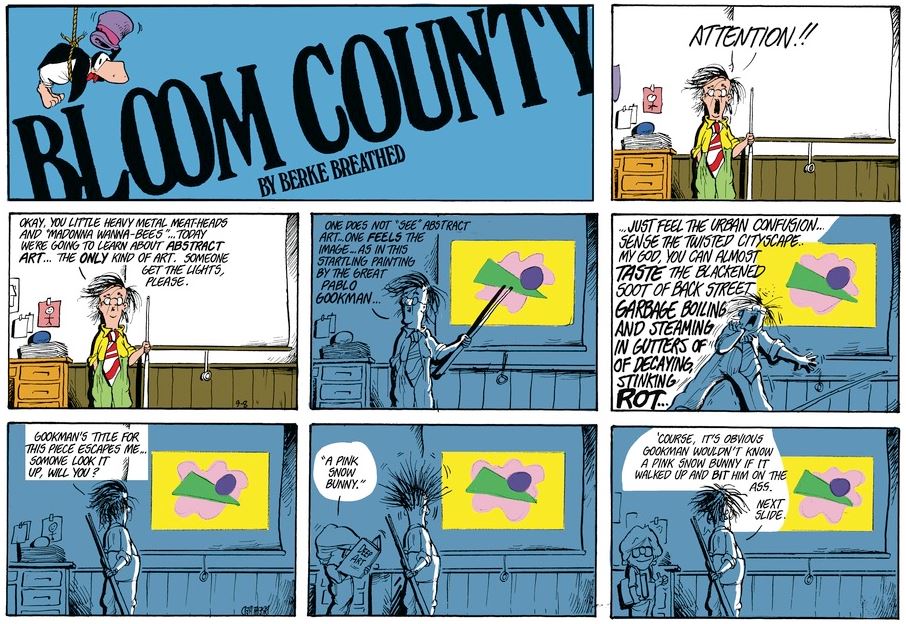

My wife and I don’t see eye-to-eye when it comes to visual art. She prefers the look of more traditional painting and sculpture, things you can look at and see recognizable people and things. I prefer more modern and abstract stuff, things that aren’t even particularly “arty” at first glance. Our trip to the Tate Britain earlier this year spawned a good round of “is this art?” discussions. They often go like this:

I think part of what I like about the more modern stuff is that it inspires in me a sense of playful wonder and awe that more traditional works don’t. I can certainly appreciate the artistry of Renaissance statuary or paintings by the great masters, but I find myself more interested in the details of what’s being depicted by them than the art itself. More modern stuff hits me right in the gut, however, and almost demands that I deal with it on its own terms, without concern for what it’s “about.”

When I was in law school I got to go to Chicago for a mock trial competition. One afternoon, a teammate and I wandered through the Art Institute, which was probably the first big art museum I’d ever been to. Around one corner we walked into the wildest thing I’d ever seen, an installation called “Clown Torture,” which:

consists of two rectangular pedestals, each supporting two pairs of stacked color monitors; two large color-video projections on two facing walls; and sound from all six video displays. The monitors play four narrative sequences in perpetual loops, each chronicling an absurd misadventure of a clown (played to brilliant effect by the actor Walter Stevens). In ‘No, No, No, No (Walter),’ the clown incessantly screams the word no while jumping, kicking, or lying down; in ‘Clown with Goldfish,’ the clown struggles to balance a fish bowl on the ceiling with the handle of a broom; in ‘Clown with Water Bucket,’ the clown repeatedly opens a door booby-trapped with a bucket of water that falls on his head; and finally, in ‘Pete and Repeat,’ the clown succumbs to the terror of a seemingly inescapable nursery rhyme. The simultaneous presentation and the relentless repetition creates an almost painful sensory overload.

This is not an inaccurate description, particularly the “almost painful sensor overload” part (and particularly if you don’t know what you’re walking into!). Now, I’m not going to say I loved “Clown Torture,” but I love the idea of it and I love that it completely unsettled me and made me think “what the fuck?” for a good long time afterward (still does, sometimes). In some instances that’s all art has to be about.

The Republic of Zaquistan is nowhere near as disturbing as “Clown Torture,” but it gives off similar “what the fuck?” vibes and so I kind of love it. It’s weird and its funny and it kind of makes you reconsider the world around you. If that’s not art I don’t know what is.