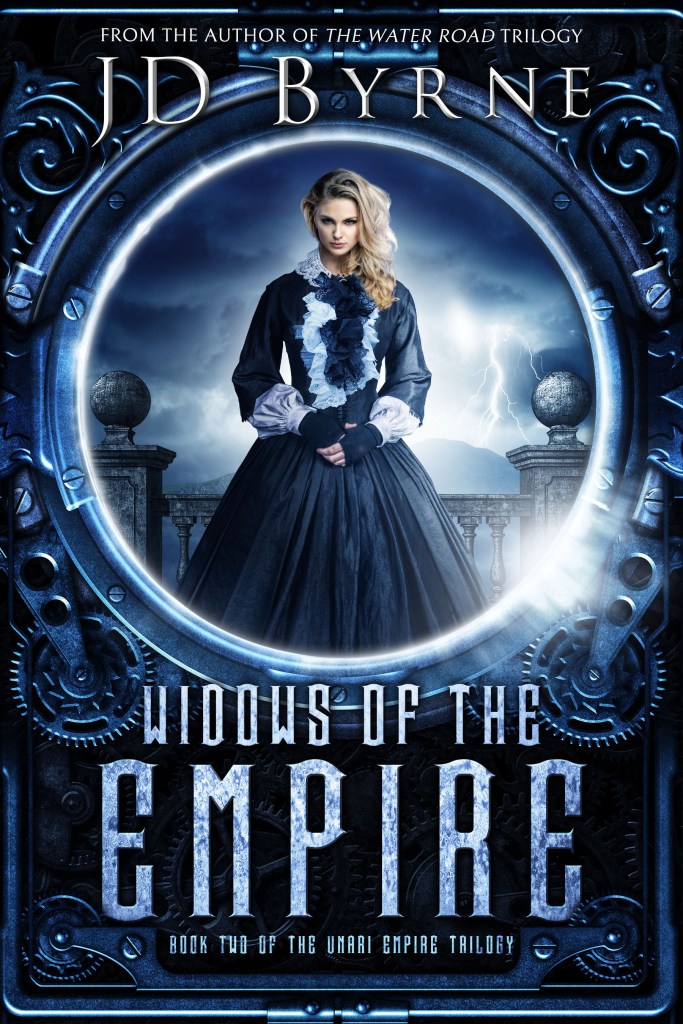

In the run-up to the release of Widows of the Empire, I wanted to highlight a few things about the world of the Unari Trilogy (for more background on the trilogy, the setting, and the characters, see this post I did before Gods of the Empire came out). Today, we look at the two largest and most important parts of the Unari Empire – the Unaru itself and the Knuria.

Being an empire, of course, the Unari Empire is composed of several disparate regions, all brought under Imperial rule. That said, there are two main ones that occupy a lot of the history of the Empire and the books in the trilogy.

The Unaru is, essentially, the original Unari Kingdom, composed of the areas around the Imperial capital of Cye. If we’re going to analogize to the Roman Empire, then Cye is Rome and the Unaru is the Italian peninsula. It’s made up of a fairly homogenous people in terms of culture and ethnicity with historical ties to the area and to the rulers who have sat in Cye for centuries.

The Knuria, by contrast, is a vast expanse of rolling farmland and rugged hills, without any real coherent cultural identity. Conquered during the expansion of the Empire, it has had second-class status ever since. If you remember when our heroes (well, some of them) wound up near a mined out bosonimum pit in Gods of the Empire, with its crumbling mining town nearby, you can get a sense of what I mean. Likewise, if you detect a bit of West Virginia in the Knuria you’re not wrong. It’s a breadbasket and extractive resource region of the Empire. Going back to the Roman Empire comparison, the Knuria is like the other parts of Europe that the Romans eventually conquered – culturally and ethnically diverse, brought to heel by force.

An aside here to say that, when I was conjuring up the Unari Empire, I was less inspired by Rome than I was by the Soviet Union. In a way, the Unaru is like Russia proper, the Knuria like the other Soviet republics – part of the USSR, but arguably separate states – and then there are other states that are within the sphere of influence. For the Empire that includes the states north of the Knuria, where some of our heroes found themselves in the second part of Gods of the Empire.

The Unaru and the Knuria are separated by two major mountain ranges. The smaller of the two, the Rampart Mountains, is north of Cye and forms the northern border of the Unaru (along with the related Rampart River). The much larger of the two, the Granite Curtain, is a huge range that runs most of the rest of the border between the Unaru and the Knuria. They’re basically impassable, a favorite hangout for outcasts and, once upon a time, gods.

Given all that, people from the Unaru look down on those from the Knuria a bit. It’s less an active discrimination than a deep-seated belief that the Knurians are just a little less developed, less civilized. It’s the urban/rural divide writ large, as there’s no place in the Knuria that can come close to Cye.

We see that a little bit with the contrast between Aton and Belwyn, our two main characters. Aton is a Cye native, an Unaru, who really hasn’t travelled outside the city (and the surrounding area) before his current work hunting down ancient artifacts of the gods. He’s “worldly” in the sense that he grew up in a large, bustling city. Belwyn, on the other hand, is Knurian, having grown up in the small lakeside town where, at the start of Widows of the Empire, she is imprisoned. That said, they both start their stories as a little bit sheltered to the realities of the wider world. They both get an education during Widows of the Empire in a way that, I hope, broadens and deepens the world they’re moving around in.

The bottom line is that the Unaru needs the Knuria and the Knuria needs the Unaru. They may not quite realize it yet.