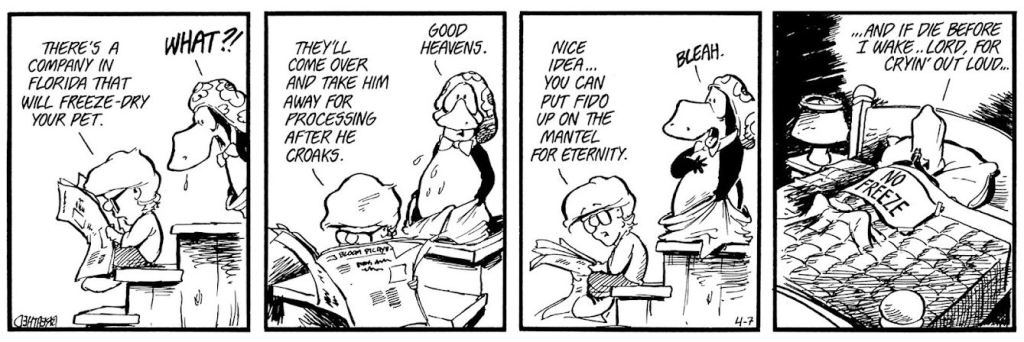

Many many years ago, there was a Bloom County cartoon in which Opus learns of new companies that allow you to freeze-dry a deceased pet and keep them around forever. His reaction was a tad overwrought:

Or at least I always thought it was. More and more, however, it’s becoming clear that we can’t just let the dead be dead, we’ve got to keep bringing them back to serve various agendas.

The most alarming recent case came out of a court in Arizona. Christopher Pelkey was killed during an incident of road rage and Gabriel Horcasitas convicted of his manslaughter. It’s pretty common in such cases to have victims (or family members of victims) give statements to the judge before sentencing about what has been lost due to whatever crime the defendant committed.

Horcasitas’ sentencing went a step further:

Ms. Wales, 47, had a thought. What if her brother, who was 37 and had done three combat tours of duty in the U.S. Army, could speak for himself at the sentencing? And what would he tell Gabriel Horcasitas, 54, the man convicted of manslaughter in his case?

The answer came on May 1, when Ms. Wales clicked the play button on a laptop in a courtroom in Maricopa County, Ariz.

A likeness of her brother appeared on an 80-inch television screen, the same one that had previously displayed autopsy photos of Mr. Pelkey and security camera footage of his being fatally shot at an intersection in Chandler, Ariz. It was created with artificial intelligence.

“It is a shame we encountered each other that day in those circumstances,” the avatar of Mr. Pelkey said. “In another life, we probably could have been friends. I believe in forgiveness and in God, who forgives. I always have and I still do.”

Reporting on the hearing has been really bad – that article quotes the defense attorney as stating (perhaps correctly) that given the wide latitude judges have at sentencing that there’s probably nothing legally wrong with it, but he also says that an appellate court might find it to be reversible error – but it’s unclear whether an objection was lodged, so who knows? Regardless, Pelkey’s reference to forgiveness beyond the grave didn’t seem to move the judge any – Horcasistas got the maximum sentence.

I can sympathize with using AI to bring a dead loved one back to life to hear them make their own plea for justice (I also think it’s ghoulish and I’ve never been a big fan of victim impact statements, but at least feel for those involved). That’s a lot harder to do when it’s part of a cynical cash grab at the expense of a dead person’s reputation.

BBC Maestro is the British broadcaster’s version of Masterclass, in which you pay to access video lectures by big names in their given fields. When it comes to mystery fiction is there a bigger name than Agatha Christie? Ah, but she’s dead. That’s no longer a problem! Thanks to the “magic” of AI and some desperate descendants:

Agatha Christie is dead. But Agatha Christie also just started teaching a writing class.

“I must confess,” she says, in a cut-glass English accent, “that this is all rather new to me.”

* * *

She has been reanimated with the help of a team of academic researchers — who wrote a script using her writings and archival interviews — and a “digital prosthetic” made with artificial intelligence and then fitted over a real actor’s performance.

“We are not trying to pretend, in any way, that this is Agatha somehow brought to life,” Michael Levine, the chief executive of BBC Maestro, said in a phone interview. “This is just a representation of Agatha to teach her own craft.”

Bullshit. Anyone could take Christie’s writings, including drafts, notes, and other non-published works, and base a writing class on it. Such a class would probably be quite useful! But it wouldn’t bring in the bucks the way having “Agatha” actually tell it to you. People are attracted to the name, which is the whole point in using it in the first place. Add in the likeness and it’s like she’s in the room with you (are the space bees, as well?).

It reminds me of the Frank Zappa hologram tour that hit the road a few years ago. A band full of Zappa alumni played live, occasionally joined by a holographic projection of Frank playing along. It was a sad gimmick. It should have been enough of a draw to hear some amazing music played live (in front of your ears!) by amazing musicians, but that wouldn’t have been enough of a draw. But Zappa there in hologram form? Well, it did sell some tickets, although the fact that it’s been largely forgotten about hints at its impact (meanwhile, Dweezil and others continue to do the man’s music justice on the live stage around the world).

And now they’re reanimating one of the most distinctive voices in movie history:

Nearly 40 years after his death, Orson Welles is back — as a disembodied AI-generated voice in location-based storytelling app Storyrabbit.

Storyrabbit, from podcast company Treefort Media, inked a partnership with the Orson Welles Estate to launch “Orson Welles Presents.” The app now features the unmistakable voice of Welles, digitally re-created using Storyrabbit’s AI technology, as an option for users to hear stories about specific locations. Using the Welles voice is free in the app until June 1, after which it will cost $4.99/month.

I mean, the idea for the app is kind of neat – it provides you with short info blurbs about specific locations based on where your phone is – but what value is added by having not-Welles give you the info? Surely the into itself is what you want, right? Maybe you don’t want it read by Gilbert Gotfried, but surely any of the numerous voice over actors or audiobook narrators out there could do the job, right?

I love history – that was my undergrad degree before I went to law school. I love the history of art, too. I’d give a lot to have been able to talk with Kurt Vonnegut or see Frank Zappa play live, but that’s never going to happen. An AI simulacrum of either of them isn’t the same thing – it’s a modern construct based largely on who we think those people were, not who they really were.

The dead are gone. They can leave us incalculable gifts, but what they can’t leave is their presence. Animating their virtual corpses in pursuit of a buck (or pound) demeans them – and us as well. Maybe Opus had it right all along.