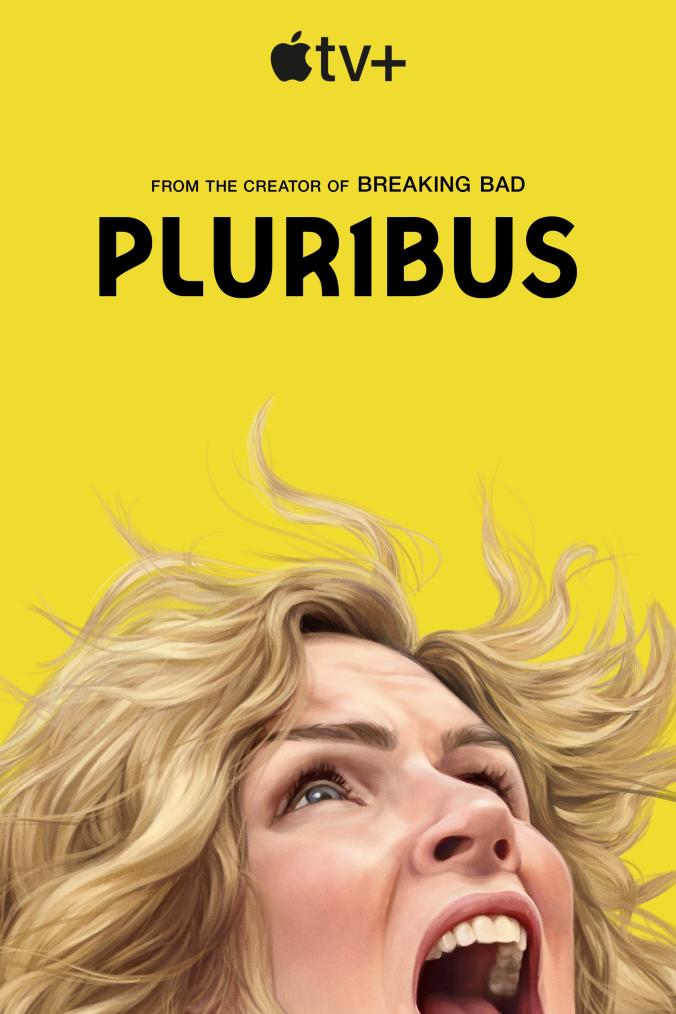

As I mentioned last month, one of my favorite TV shows from last year was Pluribus, from Breaking Bad/Better Call Saul creator Vince Gilligan.

Rhea Seahorn (also of Better Call Saul) stars as Carol, a best-selling but unfulfilled romantacy author who turns out to be one of about a dozen people in the world who can resist an alien virus-type-device that transforms the rest of Earth’s population into a gigantic hive mind. Some people also can’t survive the transformation process, including Carol’s wife.

None of this can constitute spoilers, by the way – it all happens in the first episode. Some of what I talk about below falls into that category, however, if you care about those kinds of things.

So Carol begins the story not just literally cut off from what is now the human experience but in grief. She’s angry about what she’s lost personally and acts on that anger. She’s not, at this point, all that tuned in to what it might mean for humanity to be a big hive mind (good or bad). Carol’s pain and anger is personal, small, and, in some ways, petty.

To her surprise, this puts Carol at odds with the rest of the dozen or so folks who haven’t been absorbed yet. While she’s pushing for fighting back, they’re largely OK with it. Not for nothing do they have connections to this new hive mind, in the form of loved ones or friends who are part of it (or are they?). Carol is all alone and that loneliness is what largely drives her.

This does start to change about midway through the season. She accepts the help that the hivemind can offer (there’s a fabulous scene where a wave of drones show up to restock a Whole Foods just so she can go shopping). She accepts the presence of a companion, a woman sent to her by the hive mind because she resembles the hero from Carol’s books (the version she always wanted to write, anyway). There’s even a kind of romantic connection that develops. None of this suggests that Carol has fundamentally changed who she is or what she thinks about the hivemind, but she’s learning to live with it.

Things come to a head when Manousos, another of the unabsorbed who had locked himself away in Paraguay, makes the long trek to New Mexico to find Carol, whose early radio pleas for help indicate she’s a kindred spirit. Always more radical than Carol, he’s chagrined to learn, when he shows up, that she appears to have lost whatever fighting spirit she once had. When he starts trying various ways to injure hivemind members (and perhaps restore their individuality) she objects.

Yet, that’s not where the end of the first season leaves us. Manousos stays in New Mexico while Carol and her companion jaunt around the world, the kind of bucket-list vacation you’ll never get to take in real life. It’s during that that she learns that the hivemind’s ultimate goal of assimilating her (along with the others) could be done without her consent. This snaps Carol out of it and she returns to the Albuquerque cul-de-sac and Manousos just in time for a crate containing an atomic bomb to be delivered. End season one.

So, in a way, Carol ends the season just where she began – committed to acting against the hivemind and, maybe, saving humanity. I saw a lot of complaints online after the season finale to the effect of “she’s the same she was from the beginning, what was the point?” It made me chuckle, since that seems to miss the entire point of the season.

To a certain extent a season of TV, or a book, is a journey you send characters on. In many instances you’re literally getting them from Point A to Point B, whether those are actual physical locations (a quest from home to a far away land) or something internal (an emotionally wounded person learning to love, etc.). But sometimes, the journey looks like it brings the character back to where they began, only the character has changed.

I hate to fall back on cliche, but sometimes the journey itself is more important than the destination. While end-of-season Carol seems like she’s basically in the same place as start-of-season Carol – s resist the hivemind! – she’s there for a different reason. Earlier Carol was reacting largely from ignorance. She wasn’t interested in listening to the few other people in her situation about whether the hivemind was good and, perhaps, worth joining voluntarily. End-of-season Carol has some perspective one what the hivemind can offer, albeit a limited one.

Carol, as a person, has grown over the course of the season. She went from essentially lashing out from pain and grief to finding a resolve to fight because of what joining the hivemind would mean to her. So while her ultimate goal appears to be the same now as at the beginning, the motivation is different. That matters, at least in fiction.

That will probably not content those who didn’t enjoy the first season of Pluribus. It was definitely a slow burn (probably helped that we binged it at the end of the season), but it was going somewhere and it was important that Carol get there. Does that make for a compelling season of TV? Not for everybody, but I was definitely down for it.