Having covered the small screen from 2025, let’s talk about the big one . . .

I had a pretty good 2025 when it came to movies. My wife and I made some effort to get out to the theater to see things on the big screen more than in the past few years, which meant I actually saw some new releases when they were actually new! Of course, the in-theater experience can be a little odd sometimes, so most of what I saw last year was at home.

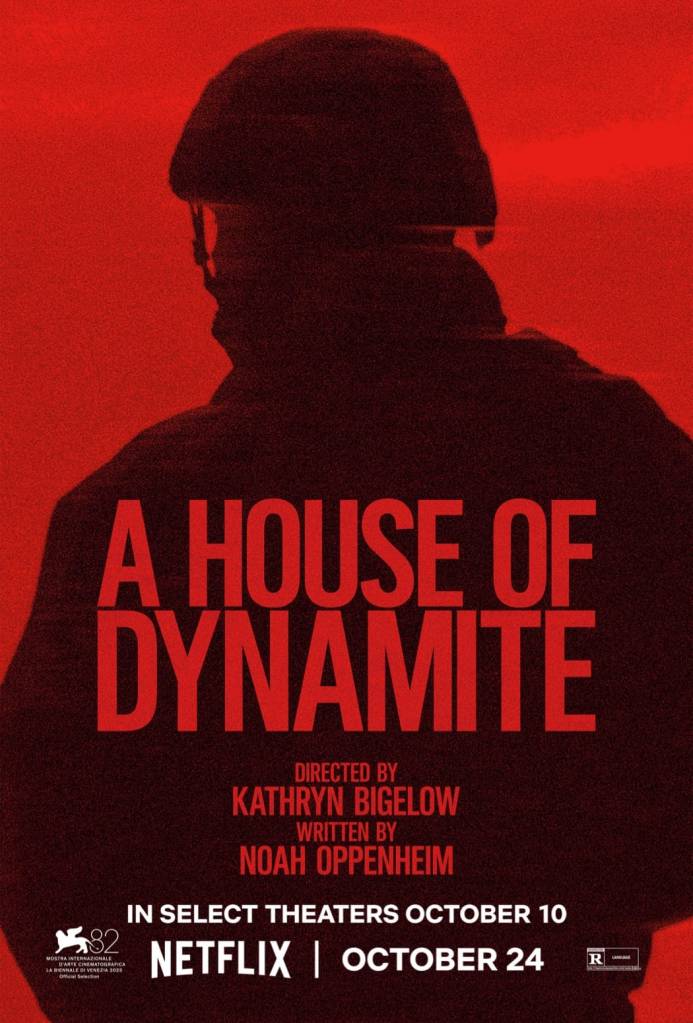

That included a movie that, while not near my favorite for 2025, has caused me to do a lot of thinking. That’s the latest from Kathryn Bigelow, A House of Dynamite.

Released on Netflix, it’s the story of a sudden, unexpected nuclear missile launch from somewhere (we never learn where) that kicks the United States’ response plans into action. It plays out in real time (three times over) as the missile heads for Chicago and a response is weighed and (maybe) retaliation launched. The time-loop structure drains some of the tension as it goes around, but I like how each time worked further up the chain of command from information gatherers to strategists and decision makers (ultimately, the president). And while the cut-to-black ending didn’t bother me as much as some people, I thought the couple of coda scenes tacked on afterwards were pointless. Regardless, what this movie did was to send me deep down a rabbit hole of fiction of the nuclear apocalypse, of which I’ll have more to say later.

Several of my favorite movies of 2025 actually came out in 2024, but I only got around to watching them after the start of the year.

That’s how I wound up seeing Anora just before it won Best Picture last year. Yeah, it was that good.

The story of a stripper/hooker who gets swept into the world of the son of a rich Russian oligarch, it’s funny, bawdy, and really sweet in equal measure. Mike Madison carried the movie as the titular character (deserved her Oscar, she did). I kind of expected to be underwhelmed by this, and maybe that’s why it hit me all the harder. I wrote some more about Anora here.

I had a better idea of what to expect from A Different Man, but it still hit pretty hard, too.

It has a simple pitch: a miserably aspiring actor with a disfiguring disease undergoes an experimental therapy to cure it, only to wind up cast in a play about a man with that condition – being advised by another man with the same condition who’s getting along quite well in life. This could have gone a very saccharine “after school special” kind of way, but it didn’t, partly due to Sebastian Stan’s amazing performance. It asks questions of identity, of what the world owes us, and how to deal. Highly recommended.

A more difficult watch, definitely, but just as highly recommended is September 5.

The particular September 5 in this case comes in 1972 at the Summer Olympics in Munich when terrorists attacked the Israeli team. This is not a broad overview of the event – for that see the 1999 documentary One Day in September, which is chilling – but focuses narrowly on how ABC Sports, who were covering the games, reacted to the situation and brought the news of it to the world. It’s very technical and, ultimately, it’s about people confronted with an astounding situation and dealing with it as best they can. Has some resonance today, no?

Home is where I normally watch documentaries – new, old, or otherwise – and 2025 was no exception. A couple were pretty disturbing, while another was uplifting in a way that made its “big screen” adaptation abysmal.

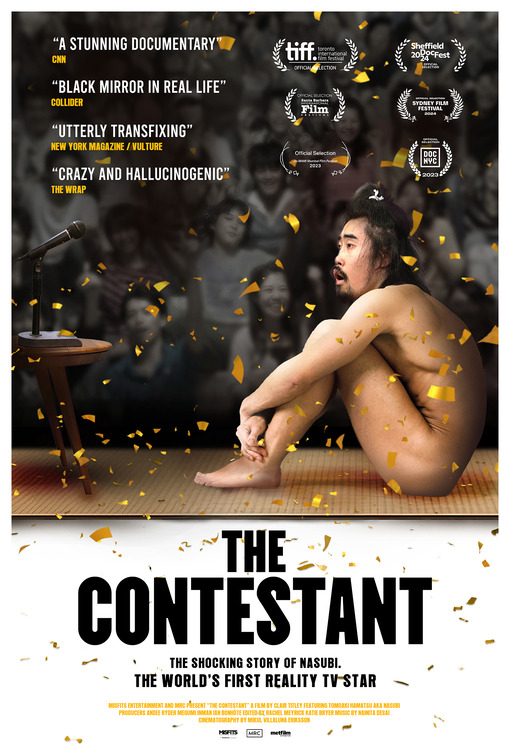

Without a doubt, one of the weirdest and saddest things I saw last year was The Contestant.

A 2023 British documentary about a late 1990s Japanese reality show, it covers the fame (infamy?) of a guy known as Nasubi (meaning “eggplant,” due to the shape of his face – and, yes, that might be where the emoji comes from) who went on a show where he lived in a tiny apartment, by himself, and had to subsist entirely on winnings from magazine sweepstakes competitions. Producers threw in a little bit of food, but he was on his own for the most part. Critically, he thought this would all be edited and broadcast later – only it was shown live (some of it streaming on the nascent internet). The whole thing is a wild indictment of just what you can get people to watch on TV and the impact it might have on the people involved.

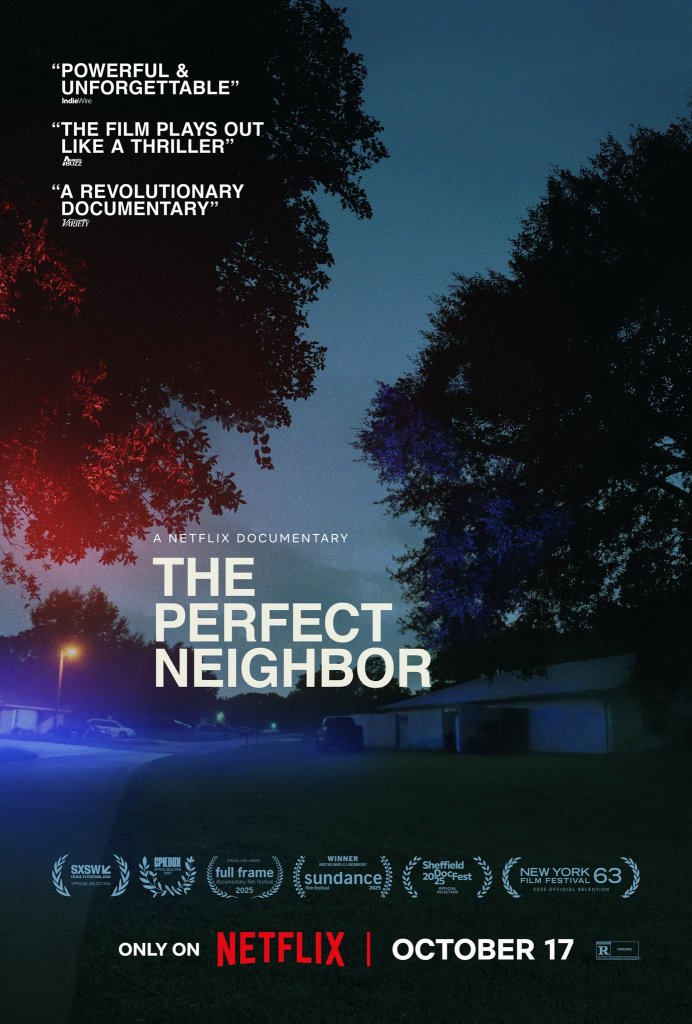

Just as sad, but for completely different reasons, was another 2025 Netflix release, The Perfect Neighbor.

It’s the story of a Florida neighborhood fully of playing kids (most of color) and the “perfect neighbor” (a racist white woman) who shot and killed their mother one night. The film is told almost entirely through body camera and dash camera footage from cops, which provides an interesting perspective (although not a completely objective one – don’t be fooled). It mostly plays out as slow motion tragedy (we know from the jump she kills somebody), but it’s really well put together and leaves you feeling like you’ve been on the corner in that neighborhood watching as things slowly simmered and then suddenly exploded.

A much happier outcome is portrayed in Next Goal Wins, a 2014 documentary about the improbable struggles of the American Samoan national soccer team.

Having been blown out by Australia 31-0 in 2001 World Cup Qualifying (a result that caused Australia to switch regions in search of more competitive games), the powers that be hired Thomas Rongen – among whose prior stops included a stretch coaching DC United (1999 Supporter’s Shield and MLS Cup winners!) – to turn things around. Which meant, maybe, winning a game during the next cycle. That happens and its as heart swelling as any game could be, but only because by that time you’re fully invested in the amateurs that make up the team (including a transgender player, highlighting Somoa’s history of more diverse views on gender identity) and Rongen himself (fighting through grief at his daughter’s death). It’s just a great story well told.

Which is more than could be said of the 2023 narrative film of the same name, starring Michael Fassbender as Rongen. I watched it by mistake (they have the same title, I rented it first) and it’s just awful, turning Rongen into a needless villain and smoothing down a lot of interesting angles. Do yourself a favor, stay away from the Hollywood version on this one.

Of course, at home is the only place I could have seen a couple of stone cold classics last year.

I didn’t even know Akira Kurosawa made a movie called High & Low until I found out last year that Spike Lee was doing a remake.

It’s the story of a wealthy businessman (who’s having issues, of course) whose son is kidnapped and he agrees to pay a ransom. Only it’s not his kid, it’s his chauffer’s taken by mistake. Will he do the right thing? That’s the first half of the movie, with the back half a tight police procedural tracking down the kidnapper. It’s wild to see Japanese cops work so selflessly, professionally, and with coordination, versus the usual rule-bending cowboys favored in American movies.

I wrote a bit about High & Low and how Lee’s joint, Highest2Lowest compare here. It’s not the masterpiece the original his, but it’s pretty good with some excellent set pieces.

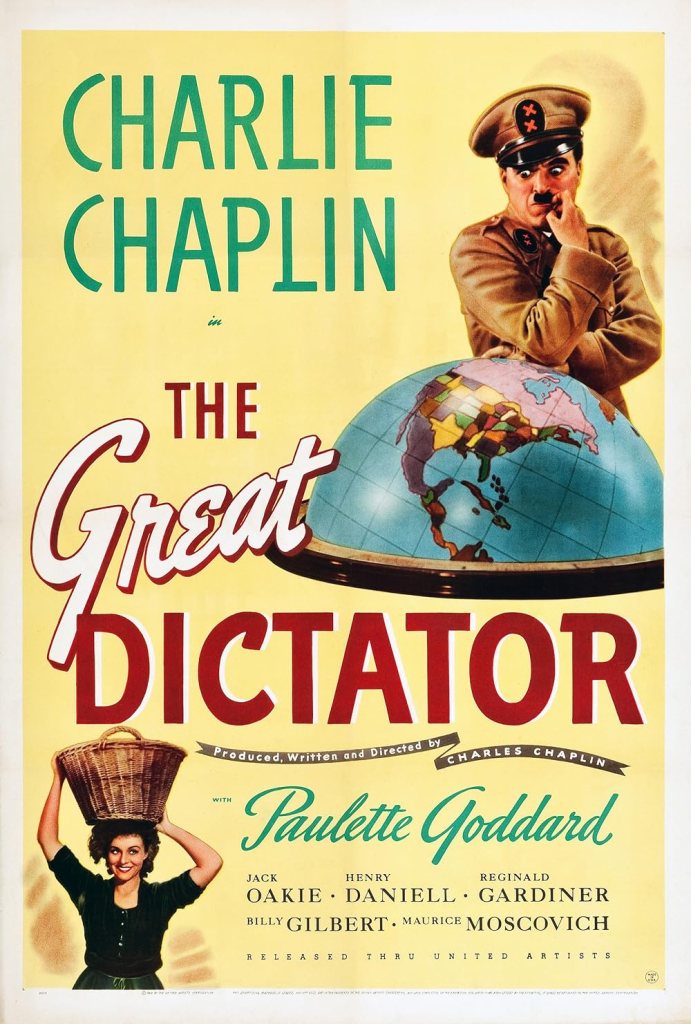

The other old movie I finally got around to seeing last year was The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin’s satire of Hitler and fascism.

Can’t imagine why that felt sadly relevant in 2025 (or 2026).

All that said, I wanted to highlight a couple of great movies I’m very glad I got to see on the big screen.

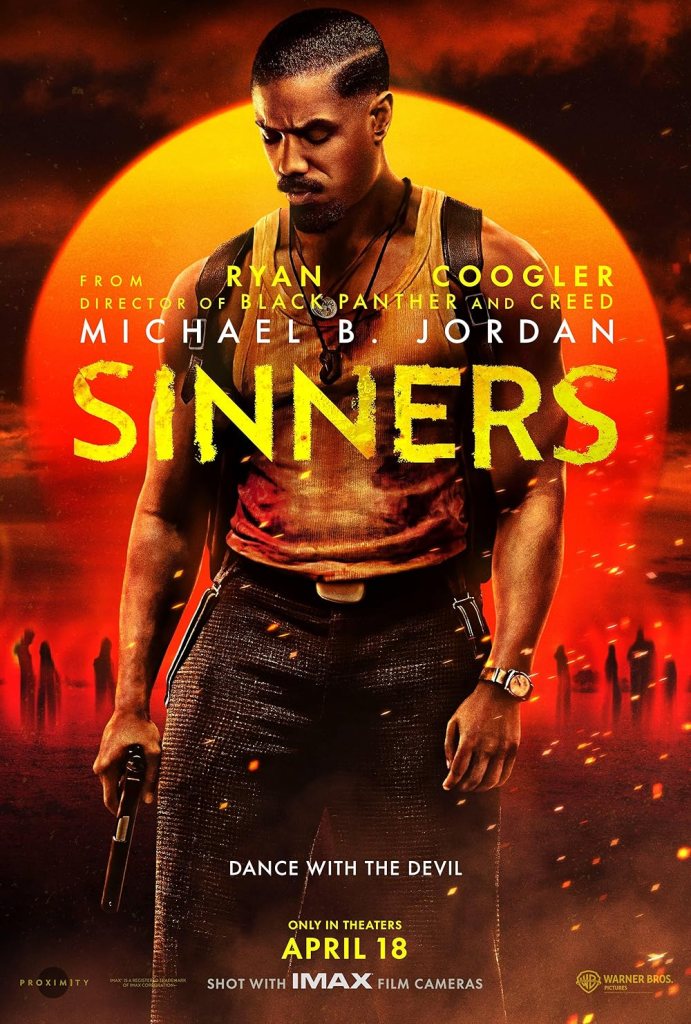

The first was Sinners, the long-simmering passion project from Ryan Coogler.

This was my favorite new movie I saw in 2025. I was a little suspicious (at one point someone said it was a musical, which, no thanks?) when I first read about it and the effusive praise it got upon release just upped my natural anti-hype reflex. It lived up to it, big time. The world building was completely immersive. The scene where the song in the juke joint turns into a rhapsody across time and culture was amazing. And Michael B. Jordan brought more reality to the one-guy-playing-two-dudes thing than most.

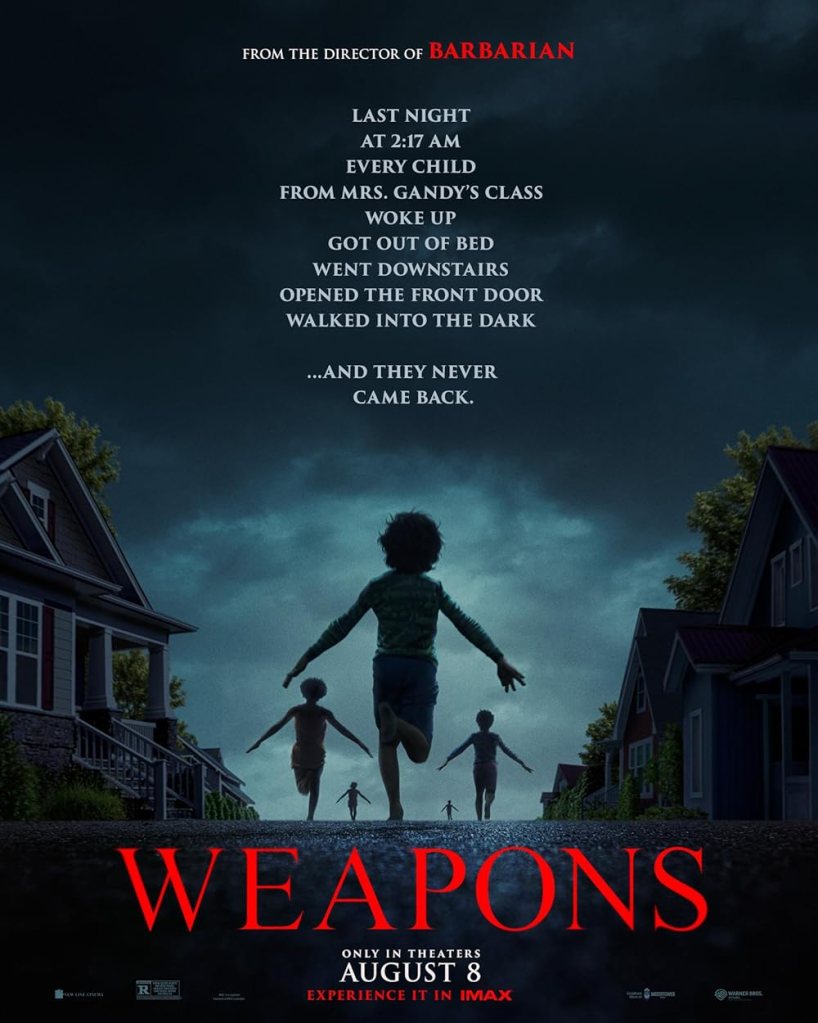

The other great new movie I saw in theaters was Weapons.

It starts with a fabulous premise – what if, one night, all the kids in a particular elementary school class just disappear (technically they run away, but still). The movie does a good job of showing how unsettled the town gets, where blame gets put initially, and the like. The fractured timeline works pretty effectively, so much so that when it lock in for the home stretch it’s kind of disappointing (shockingly hilarious violence excepted). Still, a pretty awesome telling, for the most part.

But, at the end of the year, it was back to the small screen to see what appears to be the current Best Picture front-runner, One Battle After Another.

This was another one that where my hype reflex kicked in, but it met the challenge, for the most part. I love Boogie Nights and There Will Be Blood so I didn’t find that it reached those heights, but it’s very good. Love the way Di Caprio’s character fails his way through the movie (although he does wind up in the right place when needed), but the supporting cast is just as good (including Chase Infinity, who plays his daughter). Johnny Greenwood’s score is, of course, great. All in all if this kind of “not his best work” Paul Thomas Anderson can make that’s really saying something.

So much for sights and sounds – next week we wind things up with words.