Revenge is a dish best served cold. – Klingon proverb

Revenge is an evergreen character motivation. Everybody, regardless of their station in life or what they do for a living, has gotten pissed off enough by someone to at least contemplate getting revenge. But how far can revenge get you in a story? Does there come a point where even the most righteous revenge starts to curdle?

I thought about this a lot while the wife and I were watching The Glory.

A South Korean drama from Netflix, it sprawls out over 16 hourish-long episodes (apparently originally released in two parts). The further on we got the less invested I was in the main character’s revenge arc – not because it wasn’t well founded, but because I had so much time to think about it.

The main character is Moon Deun-eun, who while in high school is constantly bullied by a group of classmates led by Park Yeon-jin. “Bully” here is really too tame of a term – they tortured the poor girl, which we see in fairly graphic detail (burning with a curling iron, for instance). They get away with it because their parents are rich and connected and Deun-eun is basically fending for herself (her father is absent, her mother worthless). After she drops out, Deun-eun struggles for a while until she dedicates her life to getting back at Yeon-jin and crew.

And she plays a long game. Over the course of years Deun-eun trains to become a teacher, eventually worming her way back into the lives of her tormentors by becoming a teacher in the school of Yeon-jin’s young daughter. From there she unwinds a pretty clever plot in which she does little herself to hurt anyone, but turns the others against one another in a way that leads to a fairly satisfying payoff. But it takes an awful long time to get there and, along the way, you start to wonder if revenge is really that great a deal, even if fully warranted.

To be fair, The Glory doesn’t let Deun-eun go quietly into the sunset when it’s all over. She’s basically stripped of her reason for living and only gets back on track by deciding to help her boyfriend get revenge on the man who killed his father. Nonetheless, your sympathies lie with Deun-eun only so far as the hot coals of revenge keep burning and I didn’t feel it at the end of 16 episodes.

Maybe it’s just the law-talking-guy in me but, in the broad view, revenge is bad. Bad for the soul, probably, but certainly bad for society. The law, in all its manifestations, is largely designed to replace systems of private justice – a.k.a. revenge. If your neighbor steals from you, you don’t break into his house and get your stuff back – you call the police or sue him. If someone kills your loved one, you don’t get to track down the offender and kill them yourself – that’s a job for the police, prosecutors, and the courts.

Emotionally revenge can be very satisfying, at least in fiction.

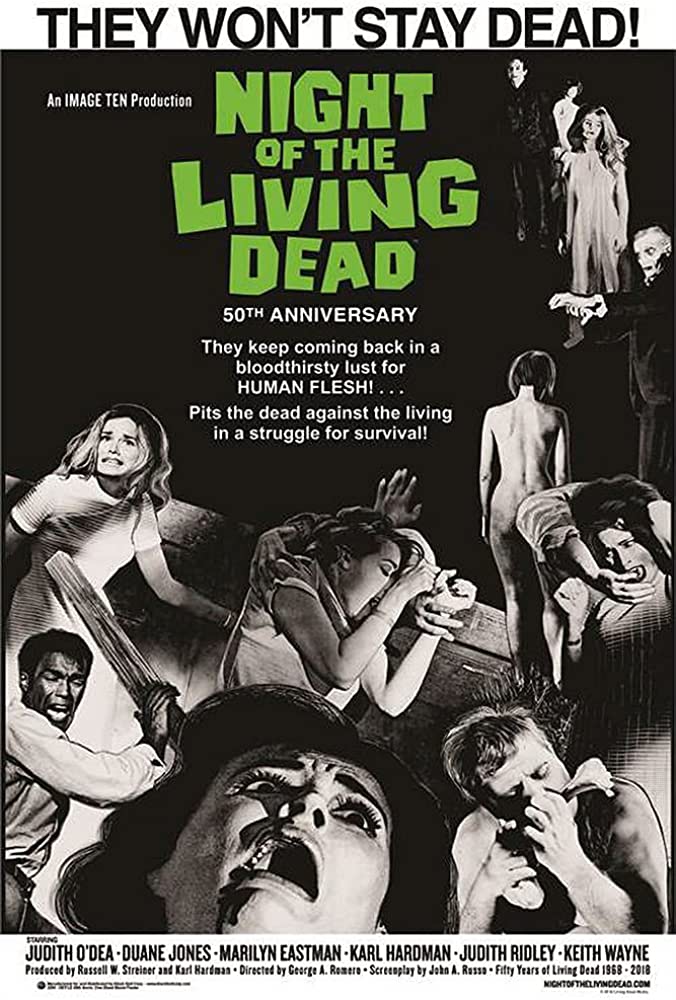

I mean, who couldn’t get on board with something like this:

On the other hand, being the better person just doesn’t have the same zip to it:

But for that very reason I think revenge works best in movies or a shorter series. There’s enough time to get you fired up and fully behind the main character’s scheme without giving you time to really think if they should be doing it in the first place. Revenge fiction works best when it harnesses that initial “this is bullshit!” reaction to learning about someone being wronged. The more time you have for that to ebb away, the less interesting the ultimate revenge is.

The quote at the top, of course, comes from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Critically, part of why that works so well is that the revenge seeker is the bad guy.