Information is not knowledge.

Knowledge is not wisdom.

Wisdom is not truth.

Truth is not beauty.

Beauty is not love.

Love is not music.

Music is THE BEST

– Mary, from the bus (via Frank Zappa, “Packard Goose”)

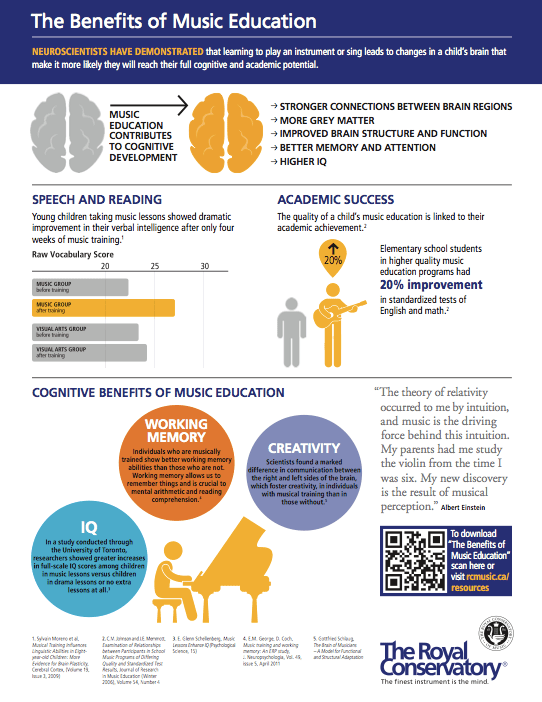

Even before the current administration’s crackdown on education, it wasn’t unusual to see band directors or other music educators arguing for, if not more funding for school music programs, then at least no more cuts. Often, music education supporters trot out a graphic like this in support of such arguments:

That’s great and it’s important that the public knows that stuff, but whenever I see it I feel like it risks turning music – and art in general – into something transactional that we do, or teach kids about, only because its boosts the bottom line down the line. Isn’t it enough to make and embrace music for its own sake?

This all came back up when I saw this article by Emily MacGregor in The Guardian:

MacGregor talks about a recent rush of books about the healing powers of music and focuses on a new BBC station called “Radio 3 Unwind”:

Programming on Unwind is light on chat, but heavy on second (i.e. slow) movements and, er, birdsong. The schedule consists mostly of playlist-type shows with names such as Mindful Mix and Classical Wind Down and features plenty of recognizable choral, piano and instrumental classics from big hitters such as Chopin, Purcell and Mozart, alongside an emphasis on new music and composers from diverse backgrounds.

Unwind’s presenters often have psychology or mindfulness credentials – and above all soothing voices. When I tune in, I find myself being encouraged to consider “the grandness of the natural world” by an authoritative baritone against strains of undulating woodwind, majestic strings, sonorous horns. “You breathe, as nature would have you breathe. You are alive.” Hmmm. A Shostakovich symphony this is not. I can’t quite shake the feeling that I’m settling in for a spa treatment.

I’m not here to poo-poo the healing power of music. Many a frustrating days at work have been made right by a drive home with the windows down, tunes blaring, and me singing along so enthusiastically I start losing my voice. Without a doubt, music can make you feel better. But isn’t it so much more?

Back to MacGregor:

The anxiety is that Unwind devalues music, so that we start thinking that it is only of value insofar as it’s useful for something else. Mightn’t Unwind encourage listeners to think classical music is little more than bland background muzak, with nothing to say? Criticism has come from all directions: the BBC has been accused of selling out, of dumbing down, of anaesthetizing listeners and of relegating classical music to the awful category of “ambient”. There’s been a rallying cry for the intrinsic value of music, music for music’s sake.

Hey, now, let’s not take shots at a foundational part of electronic music, shall we?

Anyway, I agree with MacGregor’s statement that she’s “allergic to the suggestion that music needs to be attached to claims about something else to be worthwhile,” I don’t necessarily see research about the benefits of music as problematic. The problem is more with a society that views anything that isn’t “productive” (where “productive” probably means economic gain) has to justify itself in some way. It should be enough to listen to a symphony or a Marillion song because it brings you pleasure, on some level.

Thus, I’ll join fully in MacGregor’s conclusion:

Where the art-for-art’s-sakers and the music-for-healing camps find common ground is in the idea that as a society we’ve lost sight of how important music is. Over the past decade, there’s been a sharp decline in UK sixth-formers studying the arts, following the government’s “strategic priority” emphasizing Stem subjects. But music is not the icing on the cake of an existence dominated by science, technology and economics; it’s (to push a metaphor too far) the rich butter whipped right through the mix. We are aural creatures, reverberating together.

Listen to Mary – music is the best.