A few weeks ago I finished up Kay Chronister’s The Bog Wife.

While doing my usual post-reading due diligence I pulled up the book’s Goodreads page to read some reviews and the follow conversation occurred:

MY WIFE: Are you going to read that?

ME: I just finished it.

MY WIFE: What did you think?

ME: *makes that pretty good/not great tilting hand gesture* Not bad. Three stars.

MY WIFE: Why do you say that?

ME: Are you going to read it, too?

MY WIFE: Probably not, if you only think it’s worth three stars.

I proceeded to explain to my wife my thoughts on the book (long story short – I liked the basic idea, but thought it was going somewhere more interesting and the ending felt rushed). At bottom, I’m glad I read it, but didn’t find it particularly compelling.

This got me thinking about the whole star-based rating system that is so prevalent these days. What’s a “good” star rating? What’s a “bad” one? Is there a better way of doing things?

It’s natural to want to rate something you’ve read, heard, or watched. At bottom the ultimate decision is one reflected by the old Siskel & Ebert system – thumbs up or down? Is this a movie you’d recommend to others or is it not? That’s all you really need to know, but such a system can give odd false positives. All you need to do is check out Rotten Tomatoes, where a “fresh” score can be the product of lots of good, but not great, reviews just as easily as hordes of fawning ones.

As an example, we got a chance to see Fantastic Four: First Steps in the theater (one with recliners for seating – not bad!). It currently has an 87% “certified fresh” rating, which makes it sound like a world beater. By contrast, reading the actual reviews (like this one from the AV Club) shows some nuance – the movie is generally good, but flawed in ways that might make some not care for it.

Given that, it’s not surprising that people will wind up trying to come up with something more “objective” (it’s not – this is art we’re talking about) and granular, something that you can use to compare works to each other.

For that, the star system has the potential to work out pretty well. Particularly if you’re using the 5-star system you see at places like Librarything, Letterboxd, and Rate Your Music. Particularly when you can give half stars (I’m looking at you, Goodreads) it helps make some really fine distinction between works. The problem is not everybody thinks the stars all mean the same thing.

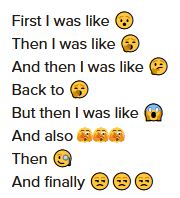

Everybody can agree that a 5-star review is a rave and a 1-star a pan (some systems even allow for the dreaded 0.5 star, which I’ve done twice at Rate Your Music). But just about anything else is a free-fire zone, it seems to me. Look at just about any work with reviews and you’ll see it. Here are some snippets from 3-star Goodreads reviews of some recent books I’ve read:

But, also:

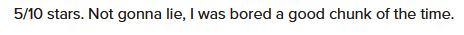

For what it’s worth, when I first started cataloging things at Rate Your Music I tried to come up with a rhyme and reason for ratings and this is what I came up with (it’s a Stickie note on my PC desktop):

As you can see, I think anything at 3 stars or over is “good.” In some ways, I respect reviews more that are a little bit skeptical, aware of flaws in something. It pains me to say this as an author, but pretty much every artistic endeavor in the history of humankind has flaws in it. Any great pillar of literature or any piece of music that makes you weak in the knees is probably flawed in some way – hell, the flaws may be part of its charm! So when I see 1-star reviews with short “this sucks!” or 5-star reviews with equally short “this is the best!” I tend to ignore them.

Don’t get me wrong – as a writer I love getting 5-star reviews! But as a reader or viewer or listener I find the less-than-loving reviews to be more interesting and, in a way, to tell me more about the work than ones that are just full of praise.

So, I suppose my takeaway here is to encourage people not to be scared away from checking out a particular work because it gets a less-than-five-star review. There’s a lot of real estate between “rules!” and “sucks!” and you may find a new favorite in there. It’s not the stars that matter, it’s the reasons for giving them that counts.

ADDENDUM: It occurred to me, as I was posting this, that this might come across as a long way of saying “my wife was wrong” in deciding not to read The Bog Wife based on my thoughts on it. One of the things about listening to reviews – or, more specifically, reviewers – is that you can learn how well your tastes and preferences match them. If you know a critic likes the same stuff you do and they love something, it’s probably worth checking out. On the other hand, if your significant other whose tastes you know is lukewarm about it so you are too? It’s all good.